|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Beyond line of sight drone operations provide great time, cost, and life-saving benefits. However, there are legal issues with flying these types of missions as well as important considerations that operators and pilots should plan for when setting up and conducting beyond line of sight drone flights. People frequently ask:

- What laws apply to beyond line of sight operations?

- What should I look for when purchasing a drone to fly far away?

- Are there certain things or features the Federal Aviation Administration wants on a drone for it to fly beyond line of sight?

- How can I obtain government approval to fly the drone far away?

If any of those questions sound familiar, you are in the right place. By the end of this article, you should have a greater understanding of the problems and solutions for drone beyond line of sight operations.

Table of Contents of Article

- 1 Benefits of Beyond Line-of-Sight Drone Operations

- 2 What is beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS)?

- 3 Aviation Laws for Beyond Line of Sight (BVLOS) Drones and Operations

- 4 Beyond Line of Sight Waivers

- 5 BVLOS Waiver Example from the FAA

- 6 BVLOS Waiver Frequently Asked Questions

- 7 Tips on Starting a Beyond Line of Sight Drone Operation

- 8 Export Laws For Beyond Line of Sight Drones

- 9 Problems With Beyond Line of Sight Flying.

- 10 Things to Look for in a BVLOS Drone

- 11 List of Beyond Line of Sight Drones

- 12 Beyond Line of Sight Communications

- 13 The Future of Beyond Line-of-Sight Laws

- 14 My BVLOS Waiver Services

- 15 Comparison of My Services to Others

- 16 Conclusion

- 17 The Part 108 Proposal: Rulemaking Committee Issues Final Report on Beyond Visual-Line-of-Sight Drone Operations

Benefits of Beyond Line-of-Sight Drone Operations

Remote Inspections

There are many types of assets in the United States that need inspecting such as powerlines, railways, pipelines, etc. You can check for failing equipment, broken equipment, vegetation encroachment, etc. You can also monitor vegetation. Greensight obtained a BVLOS waiver to monitor golf courses. If you really want to optimize operations, consider doing beyond-line-of-sight operations with a drone-in-a-box solution for fixed assets. You don’t waste time driving back and forth to the location. Check out my huge article on drones in a box. You can install the drone in a box at the assets and they can do remote inspections, perimeter security, etc. Unfortunately, drone in a box doesn’t work so great for other types of beyond-line-of-sight operations such as disaster response, where you have no idea where a tornado will touch down.

Better Economics

Time is money and flying a drone further and longer allows for greater efficiency. You don’t have to reposition the pilot on the ground. For each foot out you obtain for linear inspections, the value increases 2x the further you go (2 miles out means a 4-mile diameter). For BVLOS over a large area, thinking mapping or drone as a first responder, your value is actually related to the area covered by the operations in a circle.

Greater Range for Smaller Drones

Visual line of sight is a distance limitation (a tether associated with the physical abilities of the pilot). Certain smaller drones, due to how small they are, can go beyond line of sight rather easily compared to bigger drones.

Emergency Response/Drone as a First Responder

Beyond line of sight operations work really well for first responders in situations like searching for missing a 6-year-old in the woods, forest fire fighting, chasing bad guys running around town, and responding to an emergency scene with eyes overhead to figure out what resources are needed.

Education (Remote Training)

You can learn to fly a drone and complete training missions by flying a drone remotely. Embry Riddle Aeronautical University has this offering. The idea is you could fly, from your home, a drone at a safe location to do certain types of training missions.

What is beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS)?

Well, it depends on who is asking.

Recreational flyers must comply with 49 USC 44809 which says, “The aircraft is flown within the visual line of sight of the person operating the aircraft or a visual observer co-located and in direct communication with the operator.”

55-pound and heavier drone pilots and government pilots flying under Part 91 must comply with 91.113(b) which says, “vigilance shall be maintained by each person operating an aircraft so as to see and avoid other aircraft.”

Pilots flying under Part 107 must comply with 107.31 which says,

(a) With vision that is unaided by any device other than corrective lenses, the remote pilot in command, the visual observer (if one is used), and the person manipulating the flight control of the small unmanned aircraft system must be able to see the unmanned aircraft throughout the entire flight in order to:

(1) Know the unmanned aircraft’s location;

(2) Determine the unmanned aircraft’s attitude, altitude, and direction of flight;

(3) Observe the airspace for other air traffic or hazards; and

(4) Determine that the unmanned aircraft does not endanger the life or property of another.

(b) Throughout the entire flight of the small unmanned aircraft, the ability described in paragraph (a) of this section must be exercised by either:

(1) The remote pilot in command and the person manipulating the flight controls of the small unmanned aircraft system; or

(2) A visual observer.

I won’t get into all of the different pros and cons of each of these 3 versions. For purposes of this article, I will use 107.31 which requires (1) an ability and (2) the exercising of that ability.

Ability

There are all sorts of things that affect a pilot’s ability:

- Buildings

- Terrain

- Vegetation

- Low light

- Sun in your eyes

- Haze/smoke/rain

- Failing eyesight

- The size of the drone.

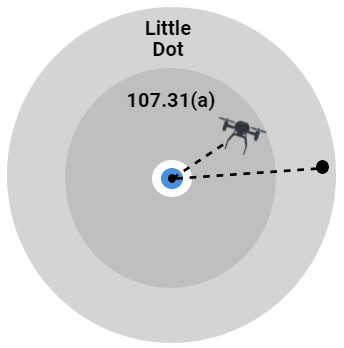

The last point is a very fascinating one. Assuming you have 20/20 vision and it’s a perfectly clear day, the dimensions of the aircraft plugged into a formula that is accepted by the FAA and NTSB creates the maximum theoretical distance the drone can actually be seen. I created a calculator here for this. For example, a 9 inch cross-section can be seen as a dot at 2,578 feet. When you play with this, you’ll notice that the bigger the drone, the further out it can be seen.

As you play with the calculator, plug in the dimensions of your drone. You should never fly beyond this number. All a clever FAA prosecutor has to do is figure out the location of the pilot and the location and the drone and plug the aircraft dimensions into the formula to say you were clearly beyond line of sight. With remote identification, this can be VERY easily done remotely.

107.31 doesn’t mean you can just see a small dot in the distance. You must be able to look at the drone and be able to “Determine the unmanned aircraft’s attitude, altitude, and direction of flight[.]” This also means 107.31(a)(2) prevents you from putting an anti-collision light visible for 3 statute miles on a drone and now say you can fly the drone out at night 3SM+ miles away because you can see the little light out on the horizon. This means 107.31(a) is a smaller distance than just seeing a little dot on the horizon.

Here are a few common situations that are beyond line of sight:

- Flying a drone from inside a trailer where the pilot cannot see outside.

- Flying the drone from inside a building where the pilot cannot see outside.

- Flying the drone as a little dot on the horizon.

- Flying the drone at night without position lights or where the position lights are so squished together they have no meaning.

Exercising of the Ability

107.3 requires the exercising of the ability by the RPIC or VO. This is pretty straightforward.

Aviation Laws for Beyond Line of Sight (BVLOS) Drones and Operations

14 CFR Part 107

We just covered 107.31 above which deals with operational restrictions.. 107.33 applies if there is a visual observer in the operation. If you are flying beyond the line of sight of the pilot, you need a 107.31 waiver. If you are flying beyond the line of sight of the visual observer, you need a 107.33 waiver. 107.205 limits 107.31 waivers from being “issued to allow the carriage of property of another by aircraft for compensation or hire.”

14 CFR 91.113(b)

This regulation applies to public aircraft operators and civil aircraft operations flying over 55 pounds. If you are flying the drone out of sight, you need a 91.113(b) certificate of waiver to fly BVLOS under Part 91.

49 USC 44807

This section of the United States Code (USC) says,

(a) In General.-Notwithstanding any other requirement of this chapter, the Secretary of Transportation shall use a risk-based approach to determine if certain unmanned aircraft systems may operate safely in the national airspace system notwithstanding completion of the comprehensive plan and rulemaking required by section 44802 or the guidance required by section 44806.

(b) Assessment of Unmanned Aircraft Systems.-In making the determination under subsection (a), the Secretary shall determine, at a minimum-

(1) which types of unmanned aircraft systems, if any, as a result of their size, weight, speed, operational capability, proximity to airports and populated areas, operation over people, and operation within or beyond the visual line of sight, or operation during the day or night, do not create a hazard to users of the national airspace system or the public; and

(2) whether a certificate under section 44703 or section 44704 of this title, or a certificate of waiver or certificate of authorization, is required for the operation of unmanned aircraft systems identified under paragraph (1) of this subsection.”

This section is how the FAA is currently determining what aircraft do NOT need to have an airworthiness certificate (55 pounds and heavier operations under Part 91) and can be used to allow for BVLOS ops. If you are flying big drones, this can done under a 44807 determination.

49 USC 44809

In order for a recreational flyer to fly in a very deregulated manner, they must comply strictly with 49 USC 44809 which requires, among other things, “(3) The aircraft is flown within the visual line of sight of the person operating the aircraft or a visual observer co-located and in direct communication with the operator.” See this article for a complete understanding of all of the recreational drone laws.

14 CFR 89.105

The FAA’s remote identification regulations are law now. The date for operators to comply and have their drones start broadcasting is September 2023. See 14 CFR 89.105. Operators have to either retrofit each aircraft, buy aircraft that can comply with remote ID, or obtain authorization or exemption from the remote ID regulations. Here is the catch for BVLOS, only aircraft capable of standard remote ID can do BVLOS. An aircraft that is only a broadcast module cannot fly BVLOS while in broadcast module mode. We could obtain an authorization or exemption but with all the headache of doing that, why not just buy another aircraft which is a standard ID aircraft? If you NEED a COA or exemption for remote ID, contact me. That will be a separate cost, but it is possible. 14 CFR 89.115(a)(2)(ii) says that for broadcast module ID aircraft “The person manipulating the flight controls of the unmanned aircraft system must be able to see the unmanned aircraft at all times throughout the operation.”

Beyond Line of Sight Waivers

Different Types of BVLOS Waivers/Configurations

Waivers are very unique to their intended operation so you have all sorts of BVLOS waivers that don’t fall into neat categories. That being said, there are some “types” of waivers that we can discuss below.

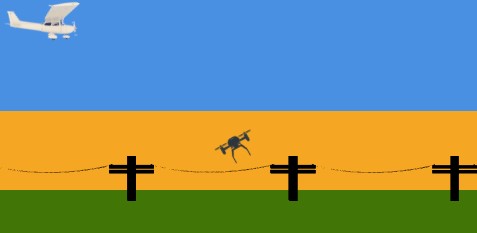

1. Shielded BVLOS Waiver

Manned aircraft have certain requirements on how low they can fly to the ground. See 14 CFR 91.119. Shielded ops mitigate air risk by flying low to the ground or close enough to infrastructure or vegetation as well as some additional mitigations to be baked into the waiver application and waiver. For example, the drone can fly in the orange corridor near the powerlines and the manned aircraft would by regulation, 91.119, be required to keep a certain distance away. Flying close to infrastructure alone doesn’t mitigate for everything. There are exceptions to this for rotorcraft (see 91.119 again) and crop dusting operations operating under Part 137. For these exceptions, extra air risk mitigations must be baked into your waiver manuals and application.

The big benefit here is you do NOT need a visual observer or pilot clearing the airspace above. This is huge because it allows for extremely long distances beyond line-of-sight flights. This type of operation works really nicely with drone in a box.

2. Drone in a box BVLOS waiver.

The idea is the drone takes off and lands in a box somewhere else from the pilot. Read my article on drone in a box operations. The big benefit of drone in a box is the aircraft is already on location. You don’t waste time driving out to the location. You can have one pilot doing flights at different locations. This type of waiver works well when you mitigate air risk by doing shielded types of operations. You can however have a visual observer on site that can be in direct communication with the pilot and use the VO to mitigate air risk when you need to fly higher than what shielded ops allow (you want to fly above the orange corridor in the picture above). So you have two types: shielded drone in a box and unshielded drone in a box.

3. Close by but out of sight BVLOS waiver.

North Carolina Department of Transportation obtained this type of waiver. The idea is NC DOT would be doing building inspections and need to fly out of sight and maybe underneath infrastructure for inspections. The press release said, “‘Inspectors will collect images using the drone instead of a snooper truck or having to suspend the inspector from the bridge,’ Spain added. ‘They’ll be able to do these inspections quickly with minimal impacts to the traveling public, like not having to close lanes of traffic for as long.'”

4. First Responder Tactical Beyond Visual Line of Sight Waivers (TBVLOS)

These are temporary 91.113(b) waivers for first responders for certain circumstances.

- The First Responder must already be flying under a valid Part 91 public COA.

- Only to be used in extreme emergency situations to safeguard human life.

- The Pilot in Command (PIC) will return to Visual Line of Sight (VLOS) operations as soon as practical or upon

the termination of the extreme emergency situation. - The PIC must not operate any higher than 50 feet above or greater than 400 feet laterally of the nearest

obstacle while operating TBVLOS. The 50 feet above an obstacle cannot exceed the 400 feet above ground

level (AGL) hard ceiling. - The UAS must remain within 1500 feet of the PIC.

- The UAS can operate, during an extreme emergency to safeguard human life, TBVLOS in controlled airspace

as long as they don’t exceed the UAS Facility Map altitude values which is a hard ceiling for these

operations. This includes operations in controlled airspace where UAS Facility Map altitude values exist, but

Low Altitude Authorization Notification Capability (LAANC) authorizations are not available (red grids).

LAANC Authorizations are NOT required to conduct TBVLOS Operations. - Operations at night, including operations at night that are in controlled airspace below the UAS Facility Map

altitude values, are allowed provided you abide by the standard provision for ‘Night Small UAS Operations’

in your COA.

Note: Emergency operations where you need to exceed the 400 feet hard ceiling or the UAS Facility Map

altitude value will require a Special Governmental Interest (SGI) COA/Waiver from the FAA’s Systems

Operations Support Center.

5. Special Governmental Interest (SGI) Waiver

While the TBVLOS waiver above was for first responders, this is for first responders AND other organizations responding to a natural disaster. FAA says:

- Firefighting (Includes Wildfire Suppression and Red Flag Warning Area Monitoring)

- Search and Rescue, Law Enforcement

- Utility or Other Critical Infrastructure Restoration

- Damage Assessments Supporting Disaster Recovery Related Insurance Claims,

- Media Coverage Providing Crucial Information to the Public

You can do an SGI either as a public aircraft operation or as a Part 107 civil aircraft operation.

FAA Joint Order 7210.3DD further elaborates:

21−4−7. UAS SPECIAL GOVERNMENTAL INTEREST (SGI) OPERATIONS

a. Public UAS and, in select cases, civil UAS operations may be needed to support activities which answer significant and urgent governmental interests, including national defense, homeland security, law enforcement, and emergency operations objectives. These operations are authorized through UAS SGI Addendums.

b. Requests for UAS SGI operations are processed as either a COA addendum, modification, or a Part 107 authorization and granted through the SGI process managed by System Operations Security, and applied under the authority of their System Operations Support Center (SOSC).

To submit an SGI waiver, fill out the Emergency Operation Request Form (MS Word) and send it to the FAA’s System Operations Support Center (SOSC) email at [email protected]. If the FAA approves you, the FAA will add an amendment to your existing COA or issue a BVLOS waiver that authorizes you to fly under certain conditions for the specified operation. If denied, operators should NOT fly outside the provisions of their existing COA or part 107. Operators have the option to amend their requests.

How Hard Is It To Obtain A BVLOS Waiver?

Setting aside TBVLOS or SGI waivers, which are really just emergency BVLOS waivers, regular non-emergency type of BVLOS waivers are a pain to obtain. The FAA has published limited information. Some data shows they have around a 98-99% rejection rate. Here is the data backing up this statement. 2018 – 1% approved (14/1392) See page 5. 2019 1.5% approved (27/1813) See page 29. Keep in mind that the data is a little dated. We can find the number of waivers currently active. You can go to this link and search for “107.31” to see how many of these waivers are active. Look at the bottom part of the table and you will see it saying “Showing 1 of XXX of XXX entries.” But that website doesn’t tell us how many have applied so as to determine the rejection rate. But don’t let that stop your plans. You should consider hiring a person who has been successful in obtaining a BVLOS waiver….like me. :)

BVLOS Waiver Example from the FAA

FAA has published some waiver examples. I have an entire article on 107 waiver examples. You can head over there and get some ideas.

BVLOS Waiver Frequently Asked Questions

Can I get one waiver for my entire company and every pilot gets to use it? Yes, this is typically the best way to do it as opposed to each pilot obtaining a waiver. You want to figure out if you want to set up a specific LLC for this operating entity or if your current business is fine. You would obtain the waiver for the business. You will have a responsible person for the company listed on the waiver. That person will be responsible for managing compliance with the waiver, the training of the pilots, etc.

How long do the waivers last? Typically, 4 years.

How many waivers can you obtain? There is no limit. You can add on overtime locations, aircraft, operations, regulations, etc. This is where it becomes important to work with someone who can keep adding on different types of aircraft, waivers, locations, etc.

How big of an area can we obtain with the waiver? That depends on your goals. The FAA has granted nationwide BVLOS waivers but they also can have considerable restrictions. You might want to go for a specific geographic area and ask for the least amount of restrictions to decrease expenses or increase operational capabilities. I would highly suggest you and I strategize about this on a phone call to optimize your expenses.

Can I combine waivers, exemptions, and authorizations such as over 400ft, swarming, Part 89 COA, etc.? The vast majority of the time it is a big NO. Most of the documents have language like this, “This Waiver may not be combined with any other waiver(s), authorizations(s), or exemption(s) without specific authorization from the FAA;” In other words, you cannot get a BVLOS waiver and then an over people waiver and say I can now fly over people while flying beyond line of sight.

The manufacturer can file the waiver for me. Is there any benefit to working with someone else to file the waiver application? Yes. Here are some reasons:

- Some waiver filers are interested in getting you a waiver with 100% reliability while I’m interested in getting you the least restrictive set of restrictions. The difference in this is huge. For example, I had a conversation with a person who obtained a BVLOS waiver. They explained they were sold an expensive detect and avoid equipment solution and they still had to use visual observers. I told them I could have obtained that same waiver using just the visual observers and that they didn’t need the equipment solution also. Yes, they received their BVLOS waiver, and the waiver filer had a happy customer, but the person also had a more expensive bill to operate. I focus on trying to find the minimum viable set of operational restrictions. If a client allows me, I’ll sometimes push the envelope to see how far we can go before we get a kickback or denial. Some manufacturers and waiver filers throw on extra restrictions or equipment requirements. Why not? They aren’t paying for it. They just want a happy customer.

- People like using me as opposed to a waiver application filed by a manufacturer because I can obtain a waiver for multiple drones from different manufacturers. I’m not captive. I don’t care what drones you buy. Want to test out a couple of drones? Let’s file the paperwork for multiple drones so you can see which one you really want to commit to long-term. I also might tell you which drone I think is better.

- I can file a waiver application without you owning a drone. Will one of the drone manufacturers do that?

- I can help you obtain waivers for other waiver operations outside of beyond line of sight (over people, swarming, etc.). Do you have other needs outside of just beyond line of sight? I can help you with those.

- I am more cost-effective when you start combining things or expanding operations as I know the manuals and can add on. This is a big problem people don’t encounter at first but later on because the 2nd application requires the manuals to be amended. That can get really time-consuming if not planned for.

How can we use this waiver as part of an overall low-capital investment strategy? Keep in mind you do NOT need to own the aircraft to obtain the waiver. You could take an asset-light approach by obtaining the waiver and then getting funding such as getting contracts (hopefully with some upfront money to buy the drone).

Can I use other aircraft in the future? If you were approved for a specific make/model, you can purchase as many of those as you want and fly as many as the waiver will allow. We don’t have the approval tied to specific aircraft serial numbers or registrations. Any make/models not in the waiver will need another waiver application filed and approved.

I don’t see my aircraft on that remote ID list. What should I do? Can we file for it? The FAA’s remote identification regulations are law now. The date for operators to comply and have their drones start broadcasting is September 2023. See 14 CFR 89.105. Operators have to either retrofit each aircraft, buy aircraft that can comply with remote ID, or obtain authorization or exemption from the remote ID regulations. Here is the catch for BVLOS, only standard ID aircraft, not broadcast ID only, can do BVLOS. If we need to obtain a remote ID COA, that will be an additional cost. There could be a benefit to that in that your drone would be essentially invisible if people were trying to detect the drone to evade security

Are there any other benefits to this waiver? Yes, (1) use it for marketing because they are pretty rare, and (2) to go and enter into contracts with companies.

Tips on Starting a Beyond Line of Sight Drone Operation

Don’t buy the aircraft and box until AFTER you obtain the waiver. You don’t need to own anything to apply or obtain a waiver. Waivers take around 30-120 calendar days to obtain. If the drone cannot get through the waiver process, you shouldn’t buy it. I don’t think any manufacturer would challenge this. Another reason why you should do the waiver first is my waiver filing service is almost always cheaper than the BVLOS drones. A waiver in hand is also important for convincing people to give you more capital to start the operation such as upper management, a bank, etc.

Hire me to get a waiver for 2 or more aircraft. Salesmen sometimes overstate the true real-world operational capabilities of aircraft. I would suggest you pick 2 candidate aircraft. We file a waiver for them. You fly those aircraft for 3-12 months to get some real-world data on which ones you like. You then make the final decision on which aircraft model you will use for the fleet.

Another variation on this is we file for 2 or more aircraft depending on the environment. For example, if a company has assets in many locations, we could identify 2 or more aircraft optimized for their environment. While the previous example is where you have two aircraft competing for all locations, this is where you pick 2 or more aircraft best optimized for their environment.

After obtaining the waiver, go and find a client who can give you a deposit. Find a client and see if you can get a deposit from the client to then buy the drone and box. Always try and buy the drone last. If that doesn’t work, enter into a contract and use that PLUS the waiver to obtain financing for the drone and equipment. You could obtain a loan from the bank and have them review the waiver approval and contract of the customer.

Lease the drone. Obtain the waiver. Have an equipment financing company purchase the drone and then provide you with a monthly lease amount (which turns CapEx into OpEx). There are companies out there that do this. It’s an alternative to the bank option.

Export Laws For Beyond Line of Sight Drones

There are numerous export laws that apply to aircraft. Here’s an entire article on export laws for unmanned aircraft that goes beyond the scope of what we will cover here. Basically, certain types of drones, technology, technical data, and services are regulated because you don’t bad guys using them or learning how to build or use them better.

You can get in trouble for sending these items outside of the country as well as INSIDE the control for selling or allowing access to certain persons in the United States. You can even get in trouble for emailing covered technical data unencrypted.

We are just going to highlight SOME of the controlled items. You should do your own due diligence.

Export Administration Regulations (EAR)

The EAR controls Non-military “Unmanned Aerial Vehicles,” (“UAVs”), unmanned “airships”, related equipment and “components” as defined in ECCN 9A012:

“a. “UAVs” or unmanned “airships”, designed to have controlled flight out of the direct ‘natural vision’ of the ‘operator’ and having any of the following:

a.1. Having all of the following:

a.1.a. A maximum ‘endurance’ greater than or equal to 30 minutes but less than 1 hour; and

a.1.b. Designed to take-off and have stable controlled flight in wind gusts equal to or exceeding 46.3 km/h (25 knots); or

a.2. A maximum ‘endurance’ of 1 hour or greater;”

Certain autopilots are controlled under 9A012.b.3. There are other controls on the development, production, technology, software, etc. related to these controlled items.

Certain types of radar are covered under the EAR.

International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR)

United States Munitions List (22 CFR 121.1 ) controls aircraft capable of flying at least 300 kilometers away and their launching and recovery equipment. Certain types of radar are covered under the ITAR. It also governs technical data and the “defense services” related to these defense items. 22 CFR 120.32 says, ” Defense service means: (1) The furnishing of assistance (including training) to foreign persons, whether in the United States or abroad in the design, development, engineering, manufacture, production, assembly, testing, repair, maintenance, modification, operation, demilitarization, destruction, processing, or use of defense articles; (2) The furnishing to foreign persons of any technical data controlled under this subchapter, whether in the United States or abroad; or (3) Military training of foreign units and forces, regular and irregular, including formal or informal instruction of foreign persons in the United States or abroad or by correspondence courses, technical, educational, or information publications and media of all kinds, training aid, orientation, training exercise, and military advice.”

Problems With Beyond Line of Sight Flying.

Detecting and Avoiding Other Aircraft (Air Risk)

Air risk can be mitigated by:

- Having a visual observer watching the sky and in direct communication with the pilot.

- Having radar (air-to-air or ground-based).

- Having a flight restriction (restricted area or temporary flight restriction) keeping manned aircraft out.

- Flying close to structures, buildings, the ground.

- Issuing a Notice to Airmen (NOTAM) to manned aircraft can know where your operation is.

- The drone or ground controller receiving ADS-B out signals from manned aircraft.

- Broadcasting out ADS-B signals. Keep in mind that this is currently not allowed unless done under certain circumstances or with an FAA certificate of authorization.

Most likely your operations will need multiple mitigations.

Keep in mind that due to the environment, you may need to find an elevated position to fly from or use some type of mechanical lift (scissor lift, cherry picker, deer stand, etc.).

Ground Risk (People and Moving Vehicles)

Here is something many people miss. Hidden inside every 107.31 waiver is an over people problem. 107.39 says,

No person may operate a small unmanned aircraft over a human being unless—

(a) That human being is directly participating in the operation of the small unmanned aircraft;

(b) That human being is located under a covered structure or inside a stationary vehicle that can provide reasonable protection from a falling small unmanned aircraft; or

(c) The operation meets the requirements of at least one of the operational categories specified in subpart D of this part.

107.145 prohibits flights over moving vehicles. Most drones don’t have airworthiness certificates or Category 2 or 3 declarations of compliance.

If you are flying over sparsely populated areas, this is not an issue but if people are around, you may need to figure out how to fly certain routes not over people or obtain a 107.39 waiver.

One way to mitigate over people is with an ASTM-compliant parachute. Parachutes need to deploy and decelerate the drone to a safe enough impact speed. That takes altitude. This means heavier drones have a higher minimum deployment height. The problem is with certain parachute systems and the weight of the drone, their minimum deployment height is at an altitude ABOVE the shielded area.

Keep in mind that there are different heights to shielded operations depending on the environment. So shielded and a parachute could work in some circumstances but not in others. For areas where shielding is low to the ground, you may have to search hard to find a solution with a low minimum deployment height.

Radio Frequency Related

Unlicensed frequencies in the United States have a limitation on their power output which means there is a radio frequency line of sight (RLOS). Typically, BVLOS happens before RLOS which is why most people don’t think about this. But when you operate in the BVLOS realm, RLOS is a big issue.

The transmitters also potentially are single points of failure for control. Jamming, frequency interference, natural obstructions, etc. One workaround is where the transmitter and receiver aggregate 4G LTE, 5G, local radio, satellite, and mesh frequencies to have the best level of reliability. See the Elsight Halo which is integrated into multiple aircraft.

Some small unmanned aircraft operate on 5.8GHz and 2.4 GHz. 2.4 has a wider fresnel zone compared to 5.8 at the same range. The benefit to this is when the aircraft is further out and lower to the ground, the 5.8GHz can have better connectivity than a 2.4. Play with the Fresnel zone calculator tool I created to see what I’m talking about. Having a drone that can switch between 2.4 and 5.8 provides greater operational flexibility when operating far out and low to the ground (like with shielded ops).

Things to Look for in a BVLOS Drone

I would highly suggest you and I chat as we plan your BVLOS operation. Keep in mind that you do NOT need to own a drone to apply for or obtain a BVLOS waiver. I would suggest you hire me and we work on crafting some mitigations for the aircraft you intend to fly before you take the leap and purchase an expensive drone.

1. Is it standard remote ID?

The aircraft must have a standard remote ID declaration of compliance listed here. https://uasdoc.faa.gov/listDocs I have instructions here on how to read these declarations of compliance. A broadcast module will NOT work. Please find your aircraft and make sure it is standard ID and the serial number is within the range listed. There is the possibility of obtaining a certificate of authorization if we need a variance but that’s extra headache.

2. Can it receive ADS-B in signals?

This isn’t a requirement for all types of BVLOS ops but for certain ones it is. Also, DJI products all have Air Sense which displays the manned aircraft on the ground controller. Multiple other manufacturers have this built in as well.

3. Does it have anti-collision lights?

Typically, you want to make the drone visible for at least 1 statute mile during the day. You can attach aftermarket add-ons. For a drone in a box solution, it must be built in unless you can have some robot stick it on to the drone.

4. Does the ground control station display enough telemetry?

Control station must display in real-time the following information: sUAaltitude, sUA position, sUA direction of flight, and sUAS flight mode.

5. Does the system provide enough warnings?

Does the ground station provide audible and visual alerts of “degraded system performance, sUAS malfunction, or loss of Command and Control (C2) link between the ground control station and the sUA[?]” This is an important point. There are 6 alerts you are trying to find out about here. Most manufacturers will say they have “alerts” but do they have visual and audible alerts of all three of those areas?

6. Can you elevate the ground controller’s antenna?

You can increase signal strength by increasing the height of the antenna of the ground controller. Unfortunately, some handheld units mean you physically have to put the person and controller in a bucket truck. There are some units out there that have transmitters you can attach to a telescoping pole.

7. What is the latency?

For purposes of detecting and avoiding other aircraft, it’s important to have a low-latency system. This becomes more important when you are transmitting over infrastructure or satellite.

8. Can it fly over people?

Go to https://uasdoc.faa.gov/listDocs and see if you can find a Declaration of Compliance (DOC) for the aircraft to allow over people. The DOC must say its for OOP (operations over people) and not just be a remote ID (RID) type of DOC approval. If you don’t have that, you will have to not fly over people. Roads also become an issue. You end up having to play Frogger. Are there any after-market parachutes that will work for this aircraft? Can that be deployed remotely? Will the range of the transmitter that activates the parachute system go farther out than your main command and control for your drone? You don’t want to lose link with the parachute system before you lose link with the drone.

9. What is the out the door cost on the overall system?

You need to figure out the final out-the-door capital expenditure (CapEx). Here are some questions you need to answer.

- Does the manufacturer charge a subscription for the software?

- What will the legal approvals cost?

- What is the main air risk mitigator? Is it a radar system? Casia G system? A human visual observer searching the sky? What are those training, installation, and ongoing subscription costs?

- Does a parachute need to be installed because you will be flying over people? What will that cost?

- Is this aircraft export-controlled? If so, you’ll need to protect it and comply with the export laws that speak to how technical data is transferred, who can have access to the aircraft, etc.

- How much do the batteries cost? How many do I need to operate in the field? Do I need a gas generator to recharge them?

10. How Well Does It Communicate At Our Proposed Ranges?

This is an important point. Certain radio frequencies are not that great low to the ground when you go farther out. If you are trying to do “shielded” ops where you fly close to trees or structures, this becomes very important. Certain environmental conditions can also really degrade system performance (e.g. Georgia pine trees). See my Fresnel Calculator to get an idea of why this is an issue. To ground truth this, obtain a BVLOS waiver and fly the drone out at those ranges. See if the radio’s RSSI drops off.

List of Beyond Line of Sight Drones

Yes, there are many multi-rotors that can fly beyond line of sight. For purposes of this, I’m really putting here aircraft that were designed to be flown at distances/durations. Keep in mind there are some aftermarket gas generators you can retrofit with some multitors to make them BVLOSable. For example, I heard about some Freefly Systems Alta X being retrofitted with a gas generator from Pegasus Aero.

Single or Muti-Rotors

- Harris H6 Hybrid

- Harris H6 Hydrone (Hydrogen Powered)

- Pegasus Aeronautics G15 Sentinel

- Skyfront Perimeter 8

- Aero Systems West. I think they can add a generator to their multi-rotors.

- AeroVironment Vapor 55

- Draganfly Commander 3 XL Hybrid (gas & electric)

- Dragan Commander 3 XL (electric)

Fixed-Wing

Beyond Line of Sight Communications

Problems

- FCC has limitations on the maximum transmission power. See 47 CFR Part 15.

- FCC has been cracking down on people asking for experimental licenses to transmit over the limits in Part 15.

- Certain types of radio frequencies may be more congested in certain areas than others (2.4 GHz near your favorite coffee shop).

- Lack of infrastructure. Cellular is great but what about the middle of nowhere? What about in the valleys?

- Certain types of terrain will cause interference.

- Certain types of operations. See Fresnel zone.

- Harmonics. Certain-sized plant leaves with water really do a great job absorbing certain frequencies.

Solutions

You may need 1 or more of the following:

- Transmitting on 2 or more frequencies.

- Telescoping pole to put the transmitting antenna on.

- Satellite communications such as the Iridium satellite system. Iridium has a white paper.

- Using dedicated frequency spectrum. The FCC has designated C-Band for beyond line of sight command and control for unmanned aircraft. If you are interested in C-band, look at uAvionix and what aircraft have their equipment in them.

- Operating in an area with infrastructure. Consider cellular coverage or if you are in North Dakota, the Vantis Network.

The Future of Beyond Line-of-Sight Laws

The FAA is presently working on regulations to allow for beyond line of sight operations.

The FAA formed an Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC) for BVLOS. The ARC issued its final report. Here is an article of the ARC report. The FAA published in the Federal Register asking for comments on certain BVLOS-related things.

My BVLOS Waiver Services

I’m presently offering service to help clients obtain a beyond-line-of-sight waiver (107.31 and 107.33).

PROCESS:

Once I receive the contract and payment, I should be able to file the paperwork in a couple of days to 2 weeks. A lot of this depends on the aircraft, the manufacturer’s documentation, manuals, documentation, etc. I’ll ask you to add me to your FAA Drone Zone account (I have instructions to help with this). I’ll log in and file the waiver application. You’ll be able to see everything. If the FAA asks any questions, you’ll see their questions. The FAA will either ask more questions, issue a denial, or issue a waiver. The overall time from filing to denial or approval will be something like 30-120 calendar days.

IMPORTANT CHARACTERISTICS

General:

-This is for civil aircraft operations. This is NOT for public aircraft operations. Keep in mind that government entities can choose to fly as civil aircraft.

-This is for under 55-pound aircraft operating under Part 107.

-The operations area cannot be too “big” because there is an air risk and ground risk analysis to this waiver. For example, if you are flying in middle-of-nowhere Kansas with few people and little air traffic around, we can ask for a pretty good size area (1-10 counties in size?) For powerlines or similar fixed assets, we can attempt 50-100 miles. For more congested areas such as many locations east of the Mississippi river, we may have to scope the operations area more narrowly. If you ask for too big of an area, the FAA analyst will say it’s too big and do it over so they can review it. Remember that there is no limit to the number of waivers you can obtain. It’s best to go and obtain a waiver application that is appropriate to the air and ground risk in the area and get the win. You will then see what I filed, and you can then file for more areas. Note this contract is only for one application being filed by me. Let me give you two scenarios. Scenario 1. If you ask for too big of an area and are denied 60 days later, you then refile and maybe get approval 60 days later. That’s 120 days to get one area. Scenario 2. If you go with my strategy of filing for a smaller appropriate area and obtain approval 60 calendar days later, you end up coming out ahead by 60 days. If you filed right away a second application upon approval of the first, at 120 days you end up with potentially more than double the area. You end up with more area and an extra 60 days to market your services and enter contracts with clients. Smaller is better when it comes to waiver filing strategy. Basically, tell me what you want and I’ll see how big of an area I can obtain on the first shot.

Aircraft:

-Only 1 make and model of aircraft. There isn’t a limit to the number of aircraft but they all must be the same make/model.

-The aircraft must have a standard remote ID declaration of compliance listed here. https://uasdoc.faa.gov/listDocs A broadcast module will NOT work. 14 CFR 89.115(a)(2)(ii) says that for broadcast module ID aircraft “The person manipulating the flight controls of the unmanned aircraft system must be able to see the unmanned aircraft at all times throughout the operation.” Please find your aircraft and make sure it is standard ID and the serial number is within the range listed. If it is not, email me back so we can discuss it. There is the possibility of obtaining a certificate of authorization if we need a variance.

– The drone must be equipped with high visibility markings and lighting to increase the conspicuity of the sUA to 3 statute miles. If you need, you can buy aftermarket anti-collision lighting and reflective tape to put onto the drone.

– Ground control station must display in real-time the following information: sUA altitude, sUA position, sUA direction of flight, and sUAS flight mode. This information must be available at all times to the remote PIC.

-Unmanned aircraft system (ground controller and/or aircraft) must audibly and visually alert the remote PIC of degraded system performance, sUAS malfunction, or loss of Command and Control (C2) link between the ground control station and the sUA. Note that some control stations might vibrate which provides noise. You make the final call if the vibration is loud enough to be audible.

Crew Related:

-Each aircraft must have 1 remote pilot and at least 1 visual observer dedicated to that aircraft ONLY. No RPIC or VO for multiple aircraft.

– Daylight only.

-The RPIC and VO must be able to see the airspace where non-participating aircraft might be flying. This means in middle-of-nowhere Kansas with no trees you could just have the RPIC and VO standing on the ground and looking for crop dusters flying low to the ground. If you are operating in a forested area, you may need to find an elevated area (e.g. top of a hill), stand on top of the truck, get on a latter, or operate from a cherry picker so as to get the RPIC and VO high enough to see the airspace. The RPIC and VO must be able to see at least a 2 statute mile radius of airspace around where the drone will be.

-If communication between the VO and the remote PIC will occur by an electronic device, as opposed to just verbally: a. The device must be continuous full-duplex, b. The remote PIC must be able to use the device hands-free, and c. There must be a reliable backup communication method. Some just choose to co-locate the RPIC and VO and they can just verbally communicate which eliminated all of this.

– Crew must file a NOTAM at least 24 hours prior to flight.

Operations Area:

– Ground risk. The operations must be over an area that is sparsely populated or controlled access unless the aircraft can fly over people. If you think the area may be more than sparsely populated, message me and we can discuss it. We may need a 107.39 waiver.

-Air Risk. The operation can only be for a specific area. We can’t get nationwide approval. The reason is the FAA analyst needs to analyze that area for airspace and ground risk. After 6 months or more of operating safely, we could MAYBE attempt a larger area or nationwide. We can discuss that later, but we need to get our foot in the door first. The area we want to fly must be beyond the following limits: 5 nautical miles from a towered airport; 3 nautical miles from a non-towered airport with instrument approach procedure; or 2 nautical miles from a non-towered airport, heliport, glider port, seaport without instrument approach procedure as shown in the Chart Supplement. If it is not in the Chart Supplement, it doesn’t count which many of those little no-name airports do NOT matter.

Deliverables:

Creating Manuals and Concept of Operations Document. I will create an operations manual that also includes normal and emergency procedures. I will also create a training manual that includes one written exam for the remote pilot in command and one written exam for the visual observer. I’ll also create a concept of operations (CONOPs), including a hazard analysis worksheet, and answers to all the Part 107 waiver safety explanation guidelines. It comes out to roughly around 145-165 pages of paperwork.

Answering FAA Questions. If the FAA asks questions, to the best of my ability, I’ll respond free of charge. This includes amending manuals and documents.

Filing 2nd Application If the First One Is Denied. If there is a denial, I will rework the original request and file it again free of charge. If there are any questions, I’ll work on those as well for free.

Cost:

For now, I am doing a fixed price of 10,000 if I have never worked on the aircraft before. I can do 5,000 for aircraft I have worked on before. So for example, I can do a BVLOS waiver for 5,000 out the door for the Matrice 300 and Mavic 3. The reason for the higher cost for newer aircraft is I have to read up a bunch on the aircraft and find out all sorts of technical issues. Remember, that price also includes following up with the FAA and refiling a 2nd time if the first time application is denied.

FAQs:

Wow. You seem pretty pricey. Why the high cost? It’s pretty simple. BVLOS waivers are a pain to get and it’s taken me years to finally dial things in and create the 100+ pages of material. Years of R&D. BVLOS waivers have around a 1-2% success rate. Here is the data backing up this statement. 2018 – 1% approved (14/1392) See page 5 https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/uas/resources/events_calendar/archive/Submitting-Operational-Waiver-Requests.pdf 2019 1.5% approved (27/1813) Page 29 https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/uas/resources/events_calendar/archive/Is_Your_UAS_Safety_Case_Ready_for_Flight-Leveraging_Research_and_Operations_to_Get_to_YES.pdf It’s free to file for a BVLOS waiver. Feel free to go ahead and take a shot. Get some denials and you’ll then appreciate the problems I had to solve. Furthermore, you can go to his link and search for “107.31” to see how many of these waivers are even active. Look at the bottom part of the table and you will see it saying “Showing 1 of XXX of XXX entries.” https://www.faa.gov/uas/commercial_operators/part_107_waivers/waivers_issued/

Are there any other benefits to this waiver? Yes, (1) use it for marketing because they are pretty rare, and (2) to go and enter into contracts with companies.

How can we use this waiver as part of an overall low-capital investment strategy? Keep in mind you do NOT need to own the aircraft to obtain the waiver. You could take an asset-light approach by obtaining the waiver and then getting contracts (hopefully with some upfront money to buy the drone). After the contract is entered into with the customer, you could choose to maybe hire as an employee a person who already owns the drone and enter into a lease with them to lease their drone for your BVLOS operations. You could also choose to finance a drone from some of the drone resellers out there. These are all ideas for keeping your costs low.

How far away can the drone fly from the remote pilot? Normally, it’s limited by your radio frequency system.

Do I need a visual observer for every flight? No. We will apply so you have the option to use a visual observer for areas higher up (typically 50-400ft AGL) not close to the ground, but for areas close to the ground and structures, you can fly without a visual observer.

Can I use other aircraft in the future? If you were apperoved for a specific make/model, you can purchase as many of those things as you want and fly as many as the waiver will allow. We don’t have the approval tied to specific aircraft serial numbers or registrations. Future aircraft will need another waiver application filed and approved.

Besides the Federal Aviation Regulations, what else should we be aware of regarding these drones? Some drones that can fly for more than 30 minutes under certain weather conditions and 60 minutes are export controlled. See ECCN 9A012.

I don’t see my aircraft on that remote ID list. What should I do? Can we file for it? The FAA’s remote identification regulations are law now. The date for operators to comply and have their drones start broadcasting is September 2023. See 14 CFR 89.105. Operators have to either retrofit each aircraft, buy aircraft that can comply with remote ID, or obtain an authorization or exemption from the remote ID regulations. Here is the catch for BVLOS, only standard ID aircraft, not broadcast ID, can do BVLOS. We could obtain an authorization or exemption but with all the headache of doing that, why not just buy another aircraft which is a standard ID aircraft? If you NEED a COA or exemption for remote ID, contact me. That will be a separate cost, but it is possible.

Why should we pick you? (1) I’m a licensed attorney so the attorney-client privilege applies to our communication. For example, if you messed up really bad, you can tell me that. The attorney-client privilege was designed so you can have a completely open conversation with your attorney. Consultants, drone manufacturers, resellers, employees, and friends are not good people to chat with when you are facing legal issues. Anything you say can be used against you. (2) I have a malpractice insurance policy that is there to protect you. Think about it. If I mess up by failing to file something, giving you the wrong information, or doing something I should not have done, that insurance policy is there to help make you whole.

I know of a company or seller that does these waivers. Why are you better? I’m constantly pushing the envelope and asking for less and less restrictions so my customers have the best waiver in terms of lower operating costs, lower capital costs, or fewer operational restrictions. Just to give you an example, one company out there files for BVLOS waivers. They require the customer to use a particular ground unit to clear the airspace. I have never used this equipment and by the people going with the other company, they end up spending 10,000+ more than me. I sell waiver services, not equipment and stuff. Another example, is some manufacturers put out templates for their sellers. These templates are restrictive and you can get better restrictions. Most people don’t know this. You are stuck with these more restrictive conditions.

What if you mess up? I have malpractice insurance.

How do I know you aren’t going to just take the money and run? Great question. Unlike most people in the drone industry, my conduct as an attorney is regulated. Here is my Florida Bar profile showing no disciplinary history and that I’m a member in good standing. https://www.floridabar.org/directories/find-mbr/profile/?num=109249 If I stiff you or act in a bad way to you, call the Florida Bar. They can then come after me and in the worse scenario, disbar me. I have skin in the game. My law license is your security.

Can I talk to one of your previous clients? My clients don’t want me handing their info out and it’s all confidential anyways. However, you can see on my Google Business Page the reviews left for me. I have a 5 Star rating with 93 reviews. No, I didn’t pay for any of them. You can also go over to regulations.gov and search the public dockets for clients I have filed exemptions for.

I want to see what the typical waiver terms and conditions will look like. Can you show them to me? I love transparency. I don’t want to be a used drone salesman and keep things hidden. In the back of the contract list the typical terms and conditions you are most likely to receive.

Have you been disciplined by the Florida Bar? Nope. You can verify this. Go to my Florida Bar page and see that it says I don’t have a discipline record.

How Do We Get Started?

Email and we’ll get started. :)

Comparison of My Services to Others

Insurance

- Rupprecht Law. I have a $1 million policy

- Skydio – ?

- Censys – ?

Provide legal advice

- Rupprecht Law – I can provide legal advice because I’m a licensed attorney

- Skydio – They are not a law firm and cannot provide legal advice. See this article for more discussion.

- Censys – They are not a law firm and cannot provide legal advice.

Attorney-Client Privileged Communications

- Rupprecht Law – Yes

- Skydio – No

- Censys – No

Pilot Certificate

- Rupprecht Law – Flight Instructor (CFI/CFII), Commercial Pilot, Certificate, and Remote Pilot

- Skydio – Jakee Stoltz is a Flight Instructor (CFI/CFII), Commercial Pilot, Certificate, and Remote Pilot. Jen Player is a Private Pilot and Remote Pilot

- Censys – ?

What aircraft?

- Rupprecht Law – I can work with any manufacturer. I’m not captive. I work with whatever aircraft you want now or in the future.

- Skydio – ?

- Censys – ?

Area of Knowledge

- Rupprecht Law – I can help with a wide variety of waiver, exemption, and authorization issues. I’ve done over people, BVLOS, moving boat, swarming, over 400 waivers and hundreds of exemptions for crop dusting and closed set cinematography for a wide area of industries. I’ve done COAs for remote ID to many different types of airspace.

- Skydio – ?

- Censys – ?

Conclusion

I wrote this article myself. I didn’t outsource it. I have a lot of information in my head (that was not in this article) and can do things faster than most. Time is money. Can you afford to not hire me? Contact me.

The Part 108 Proposal: Rulemaking Committee Issues Final Report on Beyond Visual-Line-of-Sight Drone Operations

by Trevor Simoneau

Dramatic changes are coming to drone operations. The highly anticipated concept of beyond visual line-of-sight (BVLOS) drone flying may finally become a reality. An Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC) has issued a final report about the topic, which includes recommendations for rulemaking. At this point, the BVLOS drone operations have made it through the first regulatory hurdle.

The purpose of this article is to highlight specifically intriguing recommendations made by the ARC to the FAA and provide analysis of some of the proposed regulatory text of what might possibly become “Part 108.”2

Download and read the complete report here.

Initial Review

In June 2021, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) formed an Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC) to address the burgeoning issue of beyond visual line-of-sight (BVLOS) uncrewed aircraft system (UAS) operations.[1] The primary goal of the committee was to “provide recommendations to the FAA for performance-based regulatory requirements to normalize safe, scalable, economically viable, and environmentally advantageous UAS BVLOS operations that are not under positive air traffic control (ATC).”[2]

This purpose statement outlines four key pillars of concern the FAA has chosen to focus on with respect to BLVOS UAS operations: economy, safety, environment, and equity.[3] On March 10, 2022, the ARC issued their final report. Amounting to 381 pages in total, the report contains a myriad of recommendations, including a framework for the FAA to commence rulemaking procedures to establish new “Part 108” regulations, which would govern BVLOS UAS operations.

The report divides the ARC’s recommendations to the FAA into seven categories:[4]

- Air & Ground Risk Recommendations

- Flight Rules Recommendations

- Aircraft & Systems Recommendations

- Operator Qualifications Recommendations

- Third Party Services Recommendations

- Environmental Recommendations

- General Recommendations

The report also proposes a new regulatory framework, 14 C.F.R. Part 108.[5] The ARC has even drafted sample text for certain Part 108 regulations. Moreover, the report includes potential regulations within Part 108 where the committee’s recommendations could explicitly be addressed.[6] However, not every recommendation is addressed specifically by one of the proposed regulations, most notably, none of the environmental and general recommendations.[7]

In total, the ARC has made 70 recommendations. Specifically:

| Category | Number |

| Air & Ground Risk | 9 recommendations |

| Flight Rules | 9 recommendations |

| Aircraft & Systems | 10 recommendations |

| Operator Qualifications | 20 recommendations |

| Third Party Services | 2 recommendations |

| Environmental | 5 recommendations |

| General | 15 recommendations |

| 70 recommendations TOTAL |

The FAA Rulemaking Process

Before diving into an analysis of the ARC’s recommendations regarding BVLOS UAS operations, it is first important to understand the FAA rulemaking process. To be clear, the Part 108 framework and proposed regulations included in the report are not presently rules; they do not carry the force of law that current regulations, such as Part 107, do. Additionally, at the time of writing, there has not yet been action taken by the FAA to implement any of the recommendations.

It is unclear when the FAA plans to commence rulemaking procedures to address the recommendations of the ARC. At the time of writing, there have been no press releases or policy statements issued by the FAA specifically addressing the timeline for BVLOS rulemaking. [Brendan Schulman Remote ID tweet reference?]. However, when they do, the process will probably look a lot like this:

- The FAA will issue a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) in the Federal Register.[8] The Federal Register is essentially the newspaper of the federal government. The NPRM will contain the new proposed BVLOS rule and other legally required information such as the FAA’s authority for issuing regulations.[9]

- After the NPRM has been issued, there will be a period allotted for the general public to submit comments about the rule. At this stage, anyone may participate in the rulemaking process by submitting a comment to the rulemaking docket via regulations.gov.

- Once the public comment period is over, the FAA will review and consider the comments and subsequently issue a final rule.[10] When the FAA does issue a final rule, the agency is legally required to also issue a statement addressing the basis and purpose for the rule.[11]

The FAA rulemaking process described above is governed under § 553 of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA).[12] It’s the same process used by the FAA several years ago when the agency first issued the proposed Part 107 regulations, the rules governing UAS operations today. Over the next year, be on the lookout for social media posts advertising a request for public comments about the proposed BVLOS rules.

Analysis of Specific Recommendations

I. Air & Ground Risk Recommendations

Air & Ground Risk Recommendation 2.2:

“The rules should be predicated on the risks of operation based on UA capability, size, weight, performance, and characteristics of the operating environment as opposed to the purpose of the operation.”

The ARC has determined that BVLOS regulations should be based on levels of risk associated with the particular characteristics of a particular UA, specifically, UA capability, size, weight, performance, and characteristics of the operating environment. The ARC notes that “risk levels are based on the strategic air and ground mitigations applied to the operation.”[13] There are four risk levels proposed by the ARC: level 3, level 2A, level 2B, and level 1.[14]

Air & Ground Risk Recommendation 2.3:

“BVLOS operations to the greatest extent possible should be allowed to occur through compliance with the regulation alone without the need for a waiver or exemption.”

This recommendation indicates the ARC’s intent for waivers to no longer be necessary for BVLOS operations once new rules are implemented. The ARC notes that each proposed risk level should allow for BVLOS operations to be conducted without waivers or exemptions.[15] Waivers or exemptions should only be necessary in certain higher-risk operations.[16]

Air & Ground Risk Recommendation 2.4:

“The FAA should encourage voluntary reporting in accordance with the UAS Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS).”

This recommendation, if included in the final rule, would aid in promoting UAS safety initiatives and foster regulatory compliance. It is unclear if participation in the voluntary reporting system would be integrated with the FAA’s compliance philosophy.[17] The ARC notes that the FAA should provide guidance on what types of information should be reported and includes flight hours and basic safety metrics as examples.[18]

Air & Ground Risk Recommendation 2.6:

“The rule should allow UAS to conduct transient flight over people. The rule should allow sustained flight over non-participants with strategic and/or technical mitigations applied.”

There is little doubt that for BVLOS operations to be successful, both transient and sustained flight over people (particularly people not involved with the BVLOS operations) will be necessary. The ARC agrees and proposes these types of operations should be permitted by the new BVLOS rule if an acceptable level of risk (ALR) is established and met. The ARC argues that “the relevant time-based exposure is what contributes the most exposure to ground risk. While the ARC strongly supports a single set of ALR values for UA operations, the ARC recommends differentiating between flights that transit populated areas for only a short duration of time… versus the exposure of a flight with characteristics of sustained flight over people.”[19] Essentially, as long as appropriate risk mitigations are applied, these operations should be permitted.

II. Flight Rules Recommendations

Flight Rules Recommendation 2.4:

“The FAA should amend FAR Rule Part 91.113(d) to give UA[20] Right of Way for Shielded Operations.”

The ARC addresses right-of-way issues for both shielded and non-shielded operations in its report.[21] A “shielded area is defined as a volume of airspace that includes 100’ above the vertical extent of an obstacle or critical infrastructure and is within 100 feet of the lateral extent of the same obstacle or critical infrastructure.”[22] The ARC observes that crewed aircraft operations in this area of airspace are rare and hazardous. Consequently, there is a low risk for UA and crewed aircraft encounters or collisions in shielded areas.[23] So, it makes sense for UAS conducting BVLOS shielded operations to have the right-of-way over all other aircraft. The ARC proposes adding a new part (4) to 14 C.F.R. § 91.113(d) reading: “(4) Uncrewed Aircraft conducing BVLOS Shielded Operations have right of way over all other aircraft.”[24]

Flight Rules Recommendation 2.6:

“The FAA should revise § 91.103 to include a new part (c) to accommodate UA operations.”

Responsibility and authority of the remote pilot in command (RPIC) is an essential component to the UAS regulatory framework. An important element of RPIC responsibility is preflight action, specifically, becoming familiar with certain aspects of the planned UAS operation before actually going flying. The ARC addresses this element and recommends modifying the existing regulatory text of 14 C.F.R. § 91.103 to include a new part requiring certain preflight action responsibilities for BVLOS operations.[25] This action would include confirming “conditions for safe operation and safe launch and landing areas by consulting relevant information, which may include weather station information, systems and sensors on-aircraft and other flight support systems.”[26]

Flight Rules Recommendation 2.7:

“The FAA should amend § 91.119 to allow UA operations below the Minimum Safe Altitude restrictions.”

Here, the ARC addresses the unique capabilities of UAS and recommends that they should be allowed to fly below the current Minimum Safe Altitude (MSA) restrictions.[27] The ARC recommends modifying the regulatory text of 14 C.F.R. § 91.119.[28] Interestingly, the ARC also suggests that its 91.119 amendment “would allow lower risk UA BVLOS to conduct certain types of higher risk crewed aircraft operations (e.g., agricultural spraying and helicopter inspections of power lines) and reduce the number of deaths that occur in these operations every year.”[29]

Flight Rules Recommendation 2.8:

“The FAA should amend FAR Rule Part 107.31 to include Extended Visual Line of Sight.”

In this recommendation, the ARC proposes that 14 C.F.R. § 107.31 should be amended to permit extended visual line of sight operations meaning that the RPIC need not maintain visual line of sight with the UAS, “but a trained crewmember has situational awareness of the airspace around the UAS.”[30] The ARC has noted that this is technically a BVLOS operation, but cites a UAS that flies on a different side of a building as the RPIC is standing or around tress as examples.[31]

III. Aircraft & Systems Recommendations

Aircraft & Systems Recommendation 2.1:

“The FAA should establish a new ‘BVLOS’ Rule which includes a process for qualification of uncrewed aircraft and systems. The rule should be applicable to uncrewed aircraft up to 800,000 ft-lb of kinetic energy in accordance with the Operating Environment Relative Risk Matrix.”

In its first aircraft and systems category recommendation, the ARC proposes that a “new alternative regulatory pathway” should be implemented to enable commercial BVLOS operations.[32] This alternative is Part 108. Regulations within Part 108, similar to the regulations contained within Part 107, will govern BVLOS UAS operations. The ARC includes several recommendations detailing what issues and operational considerations should be included in Part 108 regulations. The ARC also recommends that the rule address maintenance, repair, modifications, and software qualifications for UA and AE.[33]

Aircraft & Systems Recommendation 2.4:

“The new rules should include UA noise certification requirements appropriate to the operating environment. Compliance should be demonstrated through a simple testing methodology.”

In considering the environmental impact of BVLOS UAS operations, the ARC recommends there should be UAS noise certification requirements included within Part 108 regulations.

Aircraft & Systems Recommendation 2.7:

“Establish a new Special Airworthiness Certification for the UAS category under Part 21.”

The ARC notes that its intent for this recommendation is for the FAA “to create a regulatory framework for UA that is similar to that of Light-Sport Category aircraft using an FAA accepted declaration of compliance to an FAA-accepted means of compliance, which includes industry standards.”[34] The ARC also comments that the proposed Part 21 Special Airworthiness Certification (SAC) is designed for commercial BVLOS operations flying in higher-risk scenarios.[35]

Aircraft & Systems Recommendation 2.8:

“The FAA should establish a Repairperson Certification for the UAS Category to perform inspection, maintenance, and repair of UAS holding SAC under this proposal.”

The ARC addresses the importance of ensuring UAS maintenance is conducted by “adequately trained” individuals by recommending the creation of a new UAS category repairperson certification. The ARC suggests that the Light-Sport Category repairperson certification could be used as a template, or the FAA might even “consider adding UAS specific training to the existing LSA course or consider offering a supplement qualified repairpersons to become qualified to work on UAS.”[36]

Aircraft & Systems Recommendation 2.10:

“The FAA should consider allowing third party test organizations to audit compliance.”

This recommendation is further addressed by the ARC in its two specific “Third Party Services” recommendations. See below.

IV. Operator Qualifications Recommendations

Operator Qualifications Recommendation 2.1:

“The FAA create a new 14 CFR Part that governs UAS BVLOS Pilot and Operator certification requirements and operating rules.”

Again, we see the ARC recommending the development of a new regulatory framework for BVLOS UAS operations. In this category of recommendations, the ARC’s focus is remote pilot certification and the logistics of BVLOS UAS operations. The ARC notes that the new rule should cover all aspects of BVLOS UAS operations not addressed by Part 107 and offers a proposed organizational structure for the new regulations.[37]

Operator Qualifications Recommendation 2.3:

“The FAA modify 14 CFR Part 107 to enable limited BVLOS operations under the existing Remote Pilot with Small UAS Rating certificate.”

The ARC proposes that the FAA should amend Part 107 to permit current remote pilots with a small UAS rating (sUAS) to participate in limited BVLOS operations. The ARC further notes that mitigation controls should be used, but the existing use of specific FAA Part 107 waivers should not be required.[38]

Operator Qualifications Recommendation 2.4:

“The FAA expand the knowledge test for the 14 CFR Part 107 Remote Pilot Certificate with Small UAS Rating to cover topics associated with EVLOS and shielded UAS operations.”

With respect to the certification of remote pilots, the ARC suggests integrating an assessment of BVLOS UAS operations to the Part 107 knowledge test (more commonly referred to as the written exam). Specifically, the ARC recommends that topics like communication and monitoring requirements for limited BVLOS operations, navigation requirements for limited BVLOS operations, and strategic and technical risk mitigations for limited BVLOS operations, among others, should all be assessed.[39]

Operator Qualifications Recommendation 2.5:

“The FAA establish a new BVLOS rating for the Remote Pilot certificate under the new 14 CFR Part.”

While limited BVLOS operations may be covered under Part 107, according to the ARC, operations that go beyond the scope of Part 107 limited BVLOS must have their own pilot certification requirements. The ARC suggests these certification requirements should be a component of the new Part 108 rules. The ARC recommends that the FAA should establish a BVLOS rating that remote pilots may obtain, similar to how private pilots may obtain an instrument rating. Additionally, the ARC supports both “direct and progressive” pathways to obtaining the BVLOS rating.[40]

Operator Qualifications Recommendation 2.9:

“Remote Pilots certificated under Part 107 that have completed a BVLOS training program certified by a public aircraft operator entity (as defined in 14 CFR Part 1) should be able to receive their BVLOS rating via online training, similar to the existing Part 107 certification pathway for current Part 61 pilots.”

One of the pathways to the BVLOS rating proposed by the ARC is similar to the current pathway for private pilots (or any Part 61 pilot) to obtain a remote pilot certificate. The ARC has considered that there are many currently certificated remote pilots who will be interested in adding the BVLOS rating. So, the ARC suggests that after completion of a BVLOS training program, current remote pilots “should be able to receive their BVLOS rating via online training.”[41]

Operator Qualifications Recommendation 2.11:

“Create two levels of Operating Certificates for commercial UAS operations: a Remote Air Carrier certificate and a Remote Commercial Operating certificate.”

Here, the ARC addresses the specific issue of BVLOS UAS operations for commercial purposes (in other words, when someone is paying you to operate a UAS BVLOS to capture images or videos, you’re operating a UAS for compensation or hire). The ARC recommends developing two different commercial operating certificate levels: a Remote Air Carrier certificate and a Remote Operating certificate. Once again, the ARC appears to be following the traditional blueprint for crewed commercial operations, which also have an Air Carrier Certificate and Operating Certificate option. The ARC proposes that these certification requirements should be established under existing Part 119 regulations and that the specific operating requirements be established under Parts 121 and 135.[42] If the FAA moves forward with this recommendation, “Part 121 drone operations” and “Part 135 drone operations” may be terms we begin hearing in the not-so-distant future.[43]

Operator Qualifications Recommendation 2.13:

“Create Operating Requirements that govern Remote Air Carrier and Remote Operating certificate holders.”

This recommendation seems, perhaps, obvious; yet here the ARC has identified the importance of the inevitable distinction between what operations may be permitted under a “Remote Air Carrier” certificate versus a “Remote Operating” certificate. Think about this distinction like you would the rules governing operations as a “Part 121 Air Carrier” as opposed to a “Part 135 Operator.” The ARC suggests adding Part 121/135 topics to the new Part 108 rule.[44] These topics would include recordkeeping and maintenance manuals, flight crew qualifications and duty limitations, aircraft requirements, upgrade and currency training, etc.[45]

Operator Qualifications Recommendation 2.14:

“Create Certification and Operating Requirements that govern Agricultural Remote Aircraft Operations.”

In the ARC’s charter, the FAA specifically required the ARC to “at a minimum… address requirements to support… precision agriculture operations, including crop spraying.”[46] So, the ARC has addressed the issue with this recommendation. The ARC recommends adding a new sub-part (G) to Part 137 regulations to govern the certification and operation of UAS for agricultural purposes.[47]

Operator Qualifications Recommendation 2.16:

“The FAA should develop tailored medical qualifications for UAS pilots and other crew positions that consider greater accessibility and redundancy options available to UAS.”

This recommendation is particularly significant. The ARC recommends that the FAA develop a new medical certificate specifically for UAS pilots. The ARC argues that establishing medical requirements for UAS crew will aid in “opening the door for extensive contributions by people who would otherwise be disqualified from piloting a crewed aircraft.”[48] So, the ARC “recommends that the FAA develop tailored medical qualifications for UAS pilots and other crew members that reflect the reduced physical requirements for flying UA… while ensuring appropriate standards of overall health necessary to perform UA crew duties.”[49] It remains unclear what the specific medical standards or regulatory text for an UA medical certificate would look like.

Operator Qualifications Recommendation 2.19: