|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

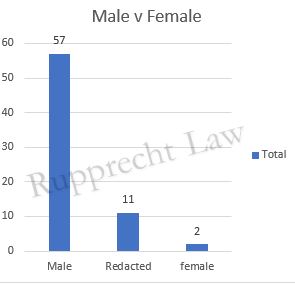

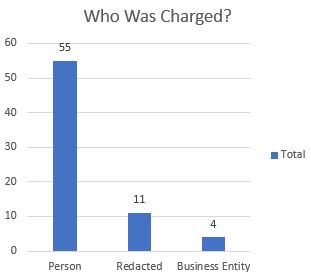

Have you ever wondered what the FAA has done in going after bad drone flyers? Have they fined remote pilots? Have they taken away their pilot certificates? All these questions and many more will be answered in this article which is designed to be the most comprehensive article on the topic. We dive into 70 enforcement actions from 2012-2020. The enforcement actions range from all sorts of things from flying near Washington D.C. to drone colliding in mid-air and causing damage to hotel property.

This article was co-written with Trevor Simoneau.

I didn’t want to drag people’s names through the mud so we scrubbed things. We just have case numbers.

Table of Contents of Article

- 1 What is an FAA Enforcement Action?

- 2 FAA Drone Enforcement Trends

- 3 How Much Can You Get Fined for Flying a Drone Illegally?

- 4 Has the FAA Revoked or Suspended a Drone Pilot’s Certificate?

- 5 Has the FAA Ever Fined a Company for Its Drone Operations?

- 6 Which Areas Are Most Active?

- 7 What Are the Most Common Drone Regulatory Violations?

- 8 Where is the FAA Really Active in Prosecuting Illegal Drone Flyers?

- 9 What Are Some of the Ways the FAA Found Out About the Illegal Flights?

- 10 What Are Some Important Lessons Revealed From These FAA Drone Enforcement Actions?

What is an FAA Enforcement Action?

Under 49 U.S. Code § 106, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is tasked with enforcing the Federal Aviation Regulations (FARs), a form of administrative law that governs all aspects of air travel in the United States including airspace, safety requirements, and remote pilot operating rules (Hamilton & Nilsson, 2020). It’s crucial to understand that FARs are not a form of criminal law but rather administrative law, meaning there are no criminal penalties associated with FAR violations. You can’t be thrown in jail for violating a FAR, however, there are a wide range of other possible consequences. These include administrative disposition actions such as being issued a warning notice or letter of correction, civil penalties, certificate action, summary seizure of aircraft, or reexamination (Hamilton & Nilsson, 2020). We will focus specifically on civil penalties and certificate actions since these are the two most common types of enforcement actions taken against remote pilots.

Civil Penalties. In many cases, FAA prosecutors choose to impose a civil penalty (fine) as opposed to taking certificate action. This occurs frequently in remote pilot enforcement cases (see enforcement data below). FAA Order 2150.3C Change 6 outlines the framework for FAA prosecutors to determine the specific dollar amount per FAR violation to issue.

Certificate Action. There are two types of certificate action an FAA prosecutor can choose between certificate suspension and certificate revocation (Hamilton & Nilsson, 2020). If the suspension is the elected sanction, the FAA prosecutor must specify for how long the pilot’s certificate will be suspended. If revocation is the elected sanction, the pilot must surrender their certificate to the FAA (Hamilton & Nilsson, 2020). FAA prosecutors will consider precedent, current FAA enforcement priorities, and individual considerations as factors when selecting either certificate suspension or revocation (Hamilton & Nilsson, 2020). Keep in mind the FAA could go after certificates of waiver, operating certificates (e.g. Parts 135 and 137), or certificates of authorization.

FAA Drone Enforcement Trends

Ya, we all figured this out.

How Much Can You Get Fined for Flying a Drone Illegally?

The exact dollar value of the proposed civil penalty (fine) varies significantly depending on the severity of your violation(s) and the extent of your illegal drone flying. It’s important to note the difference between “proposed penalties” and “settled penalties”. If the FAA chooses to pursue an enforcement case against you and has selected a civil penalty as the sanction, you will receive a “Notice of Proposed Civil Penalty” outlining your specific violations and the dollar value of the proposed civil penalty. Sometimes, an aviation or UAS attorney is able to reduce the amount of a proposed penalty, reaching an agreement with the FAA prosecutor for a fine that is less than the amount proposed by the FAA. This is the “settled penalty”.

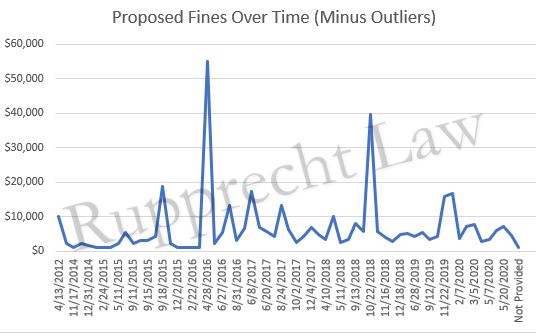

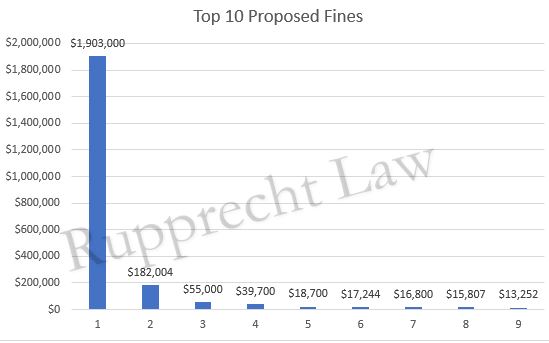

The highest fine ever was the Skypan case of 1.9 million. Here is the data of the rest of the cases minus the Skypan and the Philadelphia Flyer cases which were outliers.

Here are the top 10 proposed fines of all time.

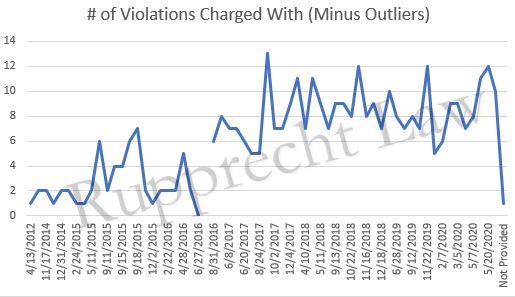

You might also want to know the typical count of charges per proposed penalty. I eliminated the large outliers (e.g. SkyPan).

Has the FAA Revoked or Suspended a Drone Pilot’s Certificate?

Yes, the FAA has brought certificate action enforcement cases against drone pilots. Of the 70UAS enforcement action cases we analyzed, 5 of them resulted in a form of certificate action.

2 cases resulted in certificate revocation.

2 cases resulted in certificate suspension (170-day and 120-day periods).

1 case resulted in certificate revocation AND a $3,000 civil penalty.

Fine or Certificate Action

Has the FAA Ever Fined a Company for Its Drone Operations?

Yes, there have been several instances where the FAA imposed a civil penalty against a company for its drone operations.

The most significant example we analyzed was the case of SkyPan International v. FAA. In 2015, the FAA proposed a $1.9 million civil penalty against SkyPan International for many total unauthorized commercial drone flights in both New York City and Chicago, all of which occurred over 2 years (FAA, 2015). The case was settled in 2017 when the FAA and SkyPan reached a $200,000 civil penalty agreement. The settlement resolved allegations in two separate cases and also included a provision requiring SkyPan to pay an additional $150,000 in the event the company ever violates an FAA regulation in the future.

Which Areas Are Most Active?

What Are the Most Common Drone Regulatory Violations?

Upon analyzing the 70 enforcement action cases, several items stood out, particularly the most common regulatory violations.

Most Frequently Violated FARs by Remote Pilots:

- You Don’t Have a Remote Pilot Certificate (107.12(a))

- Careless or Reckless (107.23(a) )

- Acting as RPIC Without Certificate. (107.12(b))

- Careless or Reckless (91.13(a))

- Drone Not Registered (107.13)

- Aeronautical Knowledge Not Current. (107.65)

- Failed to Preflight. (107.49(a))

- Posed Undue Hazard. (107.19(c))

- RPIC Failed to Ensure Compliance With Regulations. (107.19(d))

- Operated in Airspace Without Authorization (107.41)

#1: 107.12(a) – Requirement for a remote pilot certificate with a small UAS rating.

Of the cases analyzed, this was by far the most frequently violated FAR. The plain text of 107.12(a) is:

“(a) Except as provided in paragraph (c) of this section, no person may manipulate the flight controls of a small unmanned aircraft system unless:

(1) That person has a remote pilot certificate with a small UAS rating issued pursuant to subpart C of this part and satisfies the requirements of § 107.65; or

(2) That person is under the direct supervision of a remote pilot in command and the remote pilot in command has the ability to take direct control of the flight of the small unmanned aircraft.”

In many cases, violators did not have the proper remote pilot certificate or identification information. As a result, FAA prosecutors cited 107.12(a) as a violation.

#2: 107.23(a) – Hazardous operation.

In the number two spot, is 107.23(a). This is the 91.13 (careless or reckless operation) equivalent for remote pilots. The plain text of 107.23(a) is:

“No person may:

(a) Operate a small unmanned aircraft system in a careless or reckless manner so as to endanger the life or property of another;”

Frequently, FAA prosecutors will add a 107.23(a) violation to an enforcement case since it’s a relatively broad regulation and the definitions of “careless” or “reckless” are solely up to the prosecutor.

#3: 107.12(b) – Requirement for a remote pilot certificate with a small UAS rating.

In the number three spot, this regulatory violation is simply the cousin of the number one contender and covers additional provisions related to remote pilot certification. The plain text of 107.12(b) is:

“(b) Except as provided in paragraph (c) of this section, no person may act as a remote pilot in command unless that person has a remote pilot certificate with a small UAS rating issued pursuant to Subpart C of this part and satisfies the requirements of § 107.65”

107.12(b) may be used as opposed to 107.12(a) when the violation does not involve an operation being directly supervised by another remote pilot in command. While its plain text is nearly identical to 107.12(a)(1), it does not include the provision prescribed by 107.12(a)(2).

#4: 91.13(a) – Careless or reckless operation.

In the fourth spot, we have 91.13(a). The plain text of this FAR is:

“(a) Aircraft operations for the purpose of air navigation. No person may operate an aircraft in a careless or reckless manner so as to endanger the life or property of another.”

#5: 107.13 – Registration

This FAR is relatively self explanatory. The plain text of 107.13 is:

“A person operating a civil small unmanned aircraft system for purposes of flight must comply with the provisions of § 91.203(a)(2) of this chapter.”

If the sUAS wasn’t properly registered with the FAA, this FAR was added to the list of violations.

#6: 107.65 – Aeronautical knowledge recency.

In the sixth spot, we have 107.65, which deals with the knowledge test and training requirements associated with possessing a remote pilot certificate. The plain text of 107.65 is:

“A person may not exercise the privileges of a remote pilot in command with small UAS rating unless that person has accomplished one of the following in a manner acceptable to the Administrator within the previous 24 calendar months:

(a) Passed an initial aeronautical knowledge test covering the areas of knowledge specified in § 107.73;

(b) Completed recurrent training covering the areas of knowledge specified in § 107.73; or

(c) If a person holds a pilot certificate (other than a student pilot certificate) issued under part 61 of this chapter and meets the flight review requirements specified in § 61.56, completed training covering the areas of knowledge specified in § 107.74.

(d) A person who has passed a recurrent aeronautical knowledge test in a manner acceptable to the Administrator or who has satisfied the training requirement of paragraph (c) of this section prior to April 6, 2021 within the previous 24 calendar months is considered to be in compliance with the requirement of paragraph (b) or (c) of this section, as applicable.”

In most circumstances, with respect to the cases we analyzed, the violations of 107.65 were most frequently incurred when the operator had let his/her certificate expire and hadn’t properly completed the necessary recurrency training.

#7: 107.49(a) – Preflight familiarization, inspection, and actions for aircraft operation.

There were violations of 107.49(a) in the cases we analyzed. This FAR covers a lot with respect to remote pilot operating rules, but section (a) deals specifically with issues relating to weather, airspace, flying over persons or property, and ground hazards. The plain text of 107.49(a) is:

“Prior to the flight, the remote pilot in command must:

(a) Assess the operating environment, considering risks to persons and property in the immediate vicinity both on the surface and in the air. This assessment must include:

(1) Local weather conditions;

(2) Local airspace and any flight restrictions;

(3) The location of persons and property on the surface; and

(4) Other ground hazards.”

When a remote pilot fails to assess any/all of these factors, they’re not only violating 107.49(a) but are also likely violating other FARs in Part 107. In many cases, 107.49(a) serves as the tip of the iceberg for additional operational violations (airspace, flying over people, etc.).

#8: 107.19(c) – Remote pilot in command.

In the eighth spot, we have section (c) of FAR 107.19. This section specifically outlines the responsibilities of the remote pilot in command with respect to ensuring no undue hazard or harm will come to other people in the event of a loss of control incident. The plain text of 107.19(c) is:

“(c) The remote pilot in command must ensure that the small unmanned aircraft will pose no undue hazard to other people, other aircraft, or other property in the event of a loss of control of the small unmanned aircraft for any reason.”

Cases that involved 107.19(c) violations often included mid-air collisions with other sUAS or aircraft, crashing into buildings, or injuring people on the ground following loss of control.

#9: 107.19(d) – Remote Pilot in command.

Like 107.19(c) in the eighth spot, 107.19(d) also relates to the responsibilities of the remote pilot in command. The plain text of 107.19(d) is:

“(d) The remote pilot in command must ensure that the small UAS operation complies with all applicable regulations of this chapter.”

If any operation whatsoever violates any other FAR, 107.19(d) is automatically violated. FAA prosecutors chose to include a violation of 107.19(d) in 19 cases.

#10: 107.41 – Operation in certain airspace.

Last, but most certainly not least, we have 107.41. This FAR is not a long one, but it’s crucially important. The plain text of 107.41 is:

“No person may operate a small unmanned aircraft in Class B, Class C, or Class D airspace or within the lateral boundaries of the surface area of Class E airspace designated for an airport unless that person has prior authorization from Air Traffic Control (ATC).”

While many of the enforcement cases analyzed involved airspace violations, 107.41 only covers Class B, C, D, and E airspace, not special use airspace.

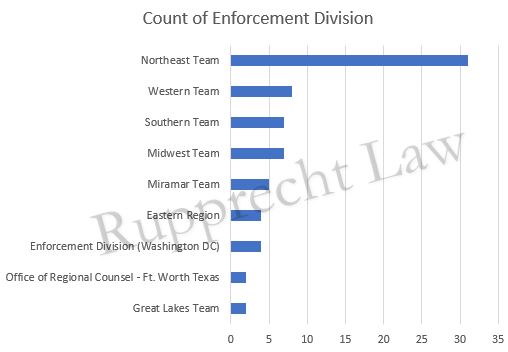

Where is the FAA Really Active in Prosecuting Illegal Drone Flyers?

The FAA is most active in pursuing enforcement actions against remote pilots when the violations involve breaching airspace without proper authorization, flying directly over people, and loss of control incidents.

Airspace. There are two primary types of airspace violations the FAA tends to prosecute: standard Class B, C, D, and E violations (as specified in 107.41) and special use airspace violations (as specified in 107.45 and 107.47). If you’re a manned aircraft pilot, when you hear the term special use airspace, you’re likely thinking of restricted, prohibited, and warning areas. While 107.45 does ban sUAS operations in prohibited and restricted areas, 107.47 is the far more frequently violated FAR. 107.47 deals with flight restrictions in the proximity of certain areas designed by notice to airmen, or NOTAM. Examples of 107.47 violations include flying inside the Washington DC SFRA and FRZ, flying inside a TFR issued for an athletic event, or flying inside a presidential TFR.

Flying over people. This violation is more common than you might think. 107.39 prohibits anyone from operating a sUAS over a human being unless that person is participating in the operation of the sUAS or located under a structure or car of some type. Frequently, when a remote pilot flies over a festival, gathering, or athletic event of some type, they’re violating 107.39. There is an exception, however, where a remote pilot may request a waiver to fly over people, as specified in 107.200 and 107.205. To learn more about the waiver process, read this article here…. That being said, none of the violators in the cases we analyzed had obtained such a waiver. Of the 70 cases we analyzed, 20 of them included violations of 107.39. For example, in one case an operator flew directly over a baseball stadium filled with 12,000 people. The proposed, and settled, civil penalty in the case was $2,200.

Loss of control. When a remote pilot loses control of an sUAS while in flight, the FAA considers this to be a severe problem and a violation of 107.23, which prohibits any person from operating an sUAS in a careless or reckless manner. Additionally, the nature of the LOC incident plays an important role in the selection of a civil penalty. When the LOC incident causes injury/harm to persons or property, the proposed civil penalty is likely to be far higher than if the sUAS simply crashed into a field. For example, consider one of the cases we analyzed….. The operator flew in Class D airspace, without authorization from ATC, over a bridge for commercial purposes while taking aerial videography of the bridge and city. The operator lost control of the sUAS and it crashed into the bridge, damaging property. Excluding the additional violations, the FAA held that the operator violated 107.23(a). The proposed civil penalty was $13,251.50, however, the settled penalty (the amount actually paid to the FAA) was $1,325.10. That’s an $11,926.40 reduction.

Stadiums. Stadiums typically have TFRs and the FAA nailed many who were flying in the TFRs near the stadiums.

What Are Some of the Ways the FAA Found Out About the Illegal Flights?

Some of the drones crashed into things (AT&T stadium, each other, and then the hotel property down below, etc.) This allowed other people to physically obtain the drones and track down the pilots. Here is some exact language:

- “The flight referenced above ended when the UAS crashed into the Space Needle near the persons working on top of the structure and near the fireworks they were installing”

- “The flight ended when the UAS crashed into a residential apartment located on the 27th floor of 20 Waterside Plaza, New York, New York which was occupied at the time of the crash. 13. The UAS shattered the apartment window causing glass to land onto the occupant of the apartment as well as inside of the apartment.”

- “The flight ended when the UAS crashed into a building”

- “ended when the sUAS crashed into a large tree located on a residential property on Black Rock Road in Phoenixville, PA where it thereafter struck a car belonging to another.”

- “you lost control of the sUAS causing it to strike and injure four individuals.”

What Are Some Important Lessons Revealed From These FAA Drone Enforcement Actions?

Before Hiring a Drone Pilot. One of the pilots had his commercial certificate suspended for 90 days yet still kept advertising on his website during the suspension he was a certificated pilot. Another one of the pilots revoked was flying was not aeronautically current. If you are a business hiring and using drone pilots, contact me so we can work on how to screen for these issues.

Intentional BVLOS Is A Violation. The Philadelphia Flyer guy was fined for intentionally flying his drone beyond the radio line of sight which the FAA held to be a violation.

Realtors Can Get Popped. One realtor in Minnesota was fined $39,700 for multiple flights. “The purpose of flight 7 was to advertise a real estate listing for” XXXXX. If you dig into the SkyPan cases, the real estate brokerage firm had to respond to subpoenas from the FAA. This caused the brokerage firm time and money complying and turning over the documents. While SkyPan’s customers did not get in trouble, they did have to spend time.