Interested in drone in a box operations? There are many questions surrounding this area such as:

- How does drone in a box work?

- What companies sell drone in a box solutions?

- What if the manufacturer of my drone doesn’t make a drone docking station? Are there any after-market boxes for my drone?

- What should I look out for when purchasing a drone in a box?

- What laws apply to drones and their docking stations?

If any of those questions hit home, this article is for you. But we won’t stop there, we’ll discuss all sorts of various issues related to drone in a box so as to make this the ultimate guide.

Table of Contents of Article

- 1 Drone In A Box Terminology

- 2 Different Drone In A Box Configurations

- 3 Uses For Drone In A Box

- 4 Laws For Drone In A Box Operations

- 5 Tips on Starting a Drone In A Box Operation

- 6 How Hard Is It To Obtain A BVLOS Waiver?

- 7 FAQS For Drone In A Box Waivers

- 8 Can you help me obtain a drone in a box BVLOS waiver?

- 9 Comparison of My Services to Others

- 10 Can You Have A Fully Autonomous Drone In A Box Solution?

- 11 Things To Consider When Purchasing A Drone In A Box Solution

- 12 Drone In A Box Companies

- 13 Conclusion

Drone In A Box Terminology

If you want to conduct your own Google search, use these terms. (Keep in mind I have a list of companies down below to save you time). There are different terms used to describe things:

- Drone docking stations

- Drone and a box

- Drone nest

- Drone nesting stations

- Drone hangar

At the end of the day, they are describing the same thing.

Different Drone In A Box Configurations

Before we go into the different uses, we need to talk about the different configurations. Some configurations are more optimized for certain missions. Take a look at the 4 main configurations.

- Fixed Tethered – This solution has an unlimited amount of flight time. There are not any issues with batteries, swapping, recharging, etc. It’s great for security in an area of interest like a front gate. But if it’s fixed, you might as well just put a pole in. But if you are at the early stages of setting things up, you could do a unit on a trailer that you just park at the front gate until the pole gets built.

- Fixed Untethered -This is what everyone thinks of for doing infrastructure inspections or drone as an emergency first responder. It has great flexibility in where it can fly but it has battery limitations (temperature, duration, recharging, etc.).

- Mobile Tethered – Multiple manufacturers have thought of the drone in the box as a modular system that would be used from the back of a vehicle. Icaros has a picture. Hoverfly also has an example here. While you think it’s all land-based, here is an example of a boat unit. You can put the unit on a trailer and deploy it. Have communication issues? No problem. You have a mobile antenna mast for communications.

- Mobile Untethered- This has a nice advantage because you can just park a trailer at some location. Keep in mind that when working with mobile units, you have to figure out how you are powering this thing. The drone has batteries but the box is going to have some type of mobile power supply. You may only have so many charges of the drone batteries from the main batteries before you need to recharge the main batteries.

If you want to break things down even further, you could add the distinction of covered (in a box) and uncovered. Some of the tethered units don’t have boxes you put the drone in but they always have some box with the power cable and battery nearby. I guess we should have called this article drone and a box.

Uses For Drone In A Box

Infrastructure Inspections

Florida Power and Light is using some drone in a box solutions to monitor their substations and power distribution grids. This is starting to get scaled out to other utilities for regular inspection.

Construction Site Monitoring (Progress, Security, Audit, OSHA, etc.)

North Carolina Department of Transportation was given approval for this.

“North Carolina transportation engineers will soon be able to inspect and monitor construction sites more safely and efficiently using docked drones flown by pilots not located at the construction site. . . . Once NCDOT completes safety testing, it plans to place drones in docking stations at projects sites across the state and use the drones to remotely monitor and provide progress reports on transportation construction projects. “This FAA waiver allows us to monitor project sites from anywhere, anytime, without the need for drone pilots to drive to sites and set up drone systems to capture and stream images,” said Becca Gallas, director of the NCDOT’s Division of Aviation, which manages the agency’s use of drones. ‘That will save time and money and increase the safety of our employees by removing the risk associated with this fieldwork.'”

Drone As A First Responder

Imagine being able to put an eye in the sky overhead on crime scenes or fires for rapid situation awareness. The 911 call would come in. The drone box would open up. The drone would rapidly take off and get to the location. Ondas Holdings is offering a solution for drones as a first responder. This drone can also be used for infrastructure inspections as well.

Another variation on this is attaching the box to a police vehicle or the Fire Chief’s suburban. The vehicle stops and the responder jumps out while the drone takes off and provides situational awareness back to dispatch who can appropriately manage limited resources. Is the fire really that bad? Does that brush fire need another fire engine? Where did the active shooter go?

Lifeguard & Shark Watcher

Drones have been used as lifeguards to drop life preservers to people needing rescue. Here is a great video showing a drone in action.

New York State is buying drones to use for shark spotting.

While these drones are being operated not in a box, imagine these being installed and remotely operated fulfilling both functions. It could perform routine monitoring. You could also use the same drone for other value adds such as monitoring beach erosion, counting wildlife, turbidity monitoring of construction on the jetty, etc.

Defibrullator AED/Narcan Delivery

Research in Sweden showed:

In this prospective clinical trial, three AED-equipped drones were placed within controlled airspace in Sweden, covering approximately 80 000 inhabitants (125 km2). Drones were integrated in the emergency medical services for automated deployment in beyond-visual-line-of-sight flights: (i) test flights from 1 June to 30 September 2020 and (ii) consecutive real-life suspected OHCAs. Primary outcome was the proportion of successful AED deliveries when drones were dispatched in cases of suspected OHCA. Among secondary outcomes was the proportion of cases where AED drones arrived prior to ambulance and time benefit vs. ambulance. Totally, 14 cases were eligible for dispatch during the study period in which AED drones took off in 12 alerts to suspected OHCA, with a median distance to location of 3.1 km [interquartile range (IQR) 2.8–3.4). AED delivery was feasible within 9 m (IQR 7.5–10.5) from the location and successful in 11 alerts (92%). AED drones arrived prior to ambulances in 64%, with a median time benefit of 01:52 min (IQR 01:35–04:54) when drone arrived first. In an additional 61 test flights, the AED delivery success rate was 90% (55/61).

Now imagine a dedicated drone in a box system designed to deliver this.

Security

Ya, we all figured this one. You could automate a perimeter patrol around a facility. This is helpful for prisons, critical infrastructure, airports, ports, etc. You could also have multiple drones being operated and being managed by 1 pilot provided you have the appropriate approvals.

Military

The military needs these solutions to quickly pop up and take a peek at what is going on over the hill or to increase their communications radio line of sight.

Mobile Communications (Cellular, etc.)

Imagine a hurricane or tornado came through wiping out power and the cellular tower. Imagine a large fire that damaged the power and infrastructure. Bring in a mobile cellular tower for communications. People can connect with their cell phones and can call 911 for help. Ericsson has already tested a mobile cellular-network-on-a-drone. CNET article said AT&T has these drones “staged already in warehouses, ready for use. ‘We have them on the West Coast for fire season, in the Southeast for hurricane season and in the Midwest for flood season[.]'” You can take these concepts and pair them with rapid-response vehicles. You could also have smaller versions you could throw in the back seat. See the Hoverfly VHA for an idea.

Laws For Drone In A Box Operations

Federal Aviation Regulations

There are two types of operators interested in drone-in-a-box operations: public aircraft operators (e.g. government entities) and civil aircraft. I won’t get into all of the important distinctions between public aircraft versus civil (you can read the distinctions here). I’m going to simply break things down into those operating under Part 107 and those operating under Part 91. This is also because some large 55-pound and heavier drones operate under Part 91 also.

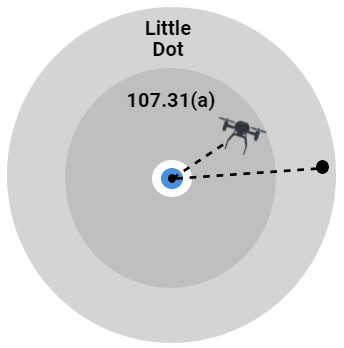

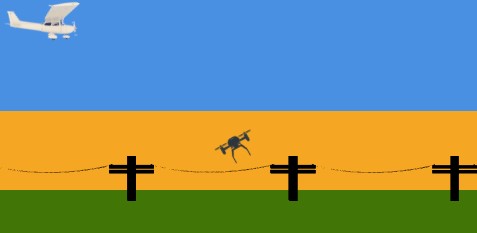

If you are flying within visual line of sight, you don’t need a beyond line of sight waiver. You can see it. The below are being discussed in the context of being operated remotely from a distance or from inside a building or trailer where they physically can’t see the aircraft.

Below are just SOME of the issues, operations have other legal issues at times so this isn’t an exhaustive list or a complete list.

Civil Aircraft Under Part 107

If you want to do a drone in a box solution under Part 107, you will need a 107.31 waiver. 107.31 says,

“With vision that is unaided by any device other than corrective lenses, the remote pilot in command, the visual observer (if one is used), and the person manipulating the flight control of the small unmanned aircraft system must be able to see the unmanned aircraft throughout the entire flight[.]”

If the remote pilot is far away, they cannot physically with their own eyes see the aircraft. No viewing the drone through a camera doesn’t count as 107.31 says, “With vision that is unaided by any device[.]”

Additionally, if you want the remote pilot to fly more than one aircraft at a time, you will need a 107.35 waiver because 107.35 says, “A person may not manipulate flight controls or act as a remote pilot in command or visual observer in the operation of more than one unmanned aircraft at the same time.”

Other waivers that should be considered would be reduced visibility and cloud clearance waivers, flying over people and moving vehicle waivers.

If doing security, consider also a remote ID COA to not broadcast and a 107.29 waiver to not use an anti-collision light at night. Those things could potentially jeopardize the security drone’s stealthiness. Or you could just leave them on to let everyone know you are there like a hiker making loud noises to let the bears know the hiker is there. Or you could do both! Leave things on and then silently and with the lights off backtrack. :)

Civil Aircraft or Public Aircraft Under Part 91

If you want to fly here doing drone in box, you’ll need a 91.113(b) waiver because 91.113(b) says,

“General. When weather conditions permit, regardless of whether an operation is conducted under instrument flight rules or visual flight rules, vigilance shall be maintained by each person operating an aircraft so as to see and avoid other aircraft. When a rule of this section gives another aircraft the right-of-way, the pilot shall give way to that aircraft and may not pass over, under, or ahead of it unless well clear.”

How can the remote pilot see the aircraft and other aircraft in the area when they are far away or physically in a building? They can’t. They need a waiver.

Export Control Regulations

Other government agencies have regulations governing unmanned aircraft. ECCN 9A012 controls aircraft that meet the following criteria.

a. “UAVs” or unmanned “airships”, designed to have controlled flight out of the direct ‘natural vision’ of the ‘operator’ and having any of the following:

a.1. Having all of the following:

a.1.a. A maximum ‘endurance’ greater than or equal to 30 minutes but less than 1 hour; and

a.1.b. Designed to take-off and have stable controlled flight in wind gusts equal to or exceeding 46.3 km/h (25 knots); or

a.2. A maximum ‘endurance’ of 1 hour or greater;

Technical Notes:

1. For the purposes of 9A012.a, ‘operator’ is a person who initiates or commands the “UAV” or unmanned “airship” flight.

2. For the purposes of 9A012.a, ‘endurance’ is to be calculated for ISA conditions (ISO 2533:1975) at sea level in zero wind.

3. For the purposes of 9A012.a, ‘natural vision’ means unaided human sight, with or without corrective lenses.

You’ll have to dive into the technicals to find out if your drone falls into this control. If you are a manufacturer, you should definitely figure this out as there are a bunch of additional controls for manufacturers.

If it is triggered, then there are extra headaches you need to be aware of when it comes to training, maintenance, repairing, interacting with the manufacturer, and getting things repaired under warranty. You can mitigate the issues. You just need to know this at the BEGINING so as to be compliant. These things might also influence your operating costs or the need for extra mitigations. I have an entire article on Drone Export Control Laws here.

Tips on Starting a Drone In A Box Operation

Fly the aircraft. I highly suggest you spend time flying the aircraft to see if it meets your needs. Either play with a demo unit somewhere or purchase/lease one for your evaluation.

Problem/Stingy Management. One roadblock I hear repeatedly is that management doesn’t want to dedicate so much money to an aircraft that needs a hard-to-obtain BVLOS waiver. You can respond that there are experienced people in this area who have had success in obtaining BVLOS waivers. I can jump on a phone call with your management to explain my experience if needed. Another fallback option, you can hire me to file for a BVLOS and then purchase the drone and box once the waiver is approved. You do not need to own anything to apply or obtain a waiver. The drawback to this is you will be waiting 30-120 calendar days while the application is being reviewed. You are losing the benefit of the drone during this time period.

Hire me to get a waiver for 2 or more aircraft and boxes. I would suggest you pick 2 candidate aircraft and boxes. We file a waiver for them. You fly those aircraft for 3-12 months to get some real-world data on which ones you like. You then make the final decision on which aircraft model you will use for the fleet.

Another variation on this is we file for 2 or more aircraft depending on the environment. For example, if a company has assets in many locations, we could identify 2 or more aircraft optimized for their environment. While the previous example is where you have two aircraft competing for all locations, this is where you pick 2 or more aircraft best optimized for their environment.

After obtaining the waiver, go and find a client who can give you a deposit. Find a client and see if you can get a deposit from the client to then buy the drone and box. If that doesn’t work, enter into a contract and use that PLUS the waiver to obtain financing for the drone and equipment. You could obtain a loan from the bank and have them review the waiver approval and contract of the customer.

Lease the drone. Obtain the waiver. Have an equipment financing company purchase the drone and then provide you with a monthly lease amount (which turns CapEx into OpEx). There are companies out there that do this. It’s an alternative to the bank option.

How Hard Is It To Obtain A BVLOS Waiver?

There are certain individuals out there who do have the knowledge and experience to have high success rates in obtaining drone in a box beyond line of sight waivers but for the average person with no aviation background, the chances of obtaining a waiver are pretty low.

Knowledge Requirement

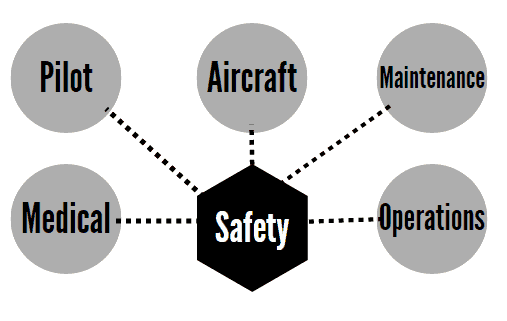

A person putting together an application will need knowledge of what the FAA is looking for in a BVLOS waiver application and how to mitigate the hazards to a safe enough level. There are numerous hazards in a BVLOS operation and the important ones, the ones the FAA really looks out for, must be addressed in the application. The FAA will most definitely want you to answer questions about how you will respond to:

- Your drone losing connection with your controller,

- A manned aircraft entering the area,

- A person or moving vehicle entering the area,

- Your drone having system failures, and

- Your degradation (voltage drop, losing GPS satellites, RSSI dropping, etc.).

Assuming you identified all of the hazards the FAA thought were important, you still must mitigate those hazards with equipment and/or operational restrictions enough to get to safe levels.

Time Consumption

A large amount of time can be consumed in putting together a waiver application. You’ll always have that pesky question in your head asking you “Did I do enough?” This leads to people putting in too much information, also known as throwing spaghetti at the wall to see what sticks method, and leads to way too much time spent in preparation of the application and the FAA reviewing the application.

The Best Solution

The FAA has published limited information. Keep in mind that the data is a little dated but it is the only data we have. The data shows around a 98-99% rejection rate – for the total population. Here is the data backing up this statement. 2018 – 1% approved (14/1392) See page 5. 2019 1.5% approved (27/1813) See page 29. For people who do waiver applications, and have been doing them for years, the success rate is much much higher. For example, I have been doing Part 107 waivers since 2016 and as of 10/19/23, I have filed 169 waiver applications and have received 12 denials. Keep in mind that this is for a wide range of waivers (BVLOS, swarm, over people, 400ft+) so my batting average is different for each type of waiver.

The amount of time to do a BVLOS waiver is considerable. If you have the time to do it, go for it. It’s an educational experience. However, your time might be best spent on other projects and hiring a person with more experience. Contact me so I can save you time and money. :)

FAQS For Drone In A Box Waivers

Can I get one waiver for my entire company and every pilot gets to use it? Yes, this is typically the best way to do it as opposed to each pilot obtaining a waiver. You want to figure out if you want to set up a specific LLC for this operating entity or if your current business is fine. You would obtain the waiver for the business. You will have a responsible person for the company listed on the waiver. That person will be responsible for managing compliance with the waiver, the training of the pilots, etc.

How long do the waivers last? Typically, 4 years.

How many waivers can you obtain? There is no limit. You can add on overtime locations, aircraft, operations, regulations, etc. This is where it becomes important to work with someone who can keep adding on different types of aircraft, waivers, locations, etc.

How big of an area can we obtain with the waiver? That depends on your goals. The FAA has granted nationwide BVLOS waivers but they also can have considerable restrictions. You might want to go for a specific geographic area and ask for the least amount of restrictions to decrease expenses or increase operational capabilities. I would highly suggest you and I strategize about this on a phone call to optimize your expenses.

Are there any other benefits to this waiver? Yes, (1) use it for marketing because they are pretty rare, and (2) to go and enter into contracts with companies.

Can I combine waivers, exemptions, and authorizations such as over 400ft, swarming, Part 89 COA, etc.? The vast majority of the time it is a big NO. Most of the documents have language like this, “This Waiver may not be combined with any other waiver(s), authorizations(s), or exemption(s) without specific authorization from the FAA;” In other words, you cannot get a BVLOS waiver and then an over people waiver and say I can now fly over people while flying beyond line of sight.

The manufacturer can file the waiver for me. Is there any benefit to working with someone else to file the waiver application? Yes. Here are some reasons:

- Some waiver filers are interested in getting you a waiver with 100% reliability while I’m interested in getting you the least restrictive set of restrictions. The difference in this is huge. For example, I had a conversation with a person who obtained a BVLOS waiver. They explained they were sold an expensive detect and avoid equipment solution and they still had to use visual observers. I told them I could have obtained that same waiver using just the visual observers and that they didn’t need the equipment solution also. Yes, they received their BVLOS waiver, and the waiver filer had a happy customer, but they also had a more expensive bill to operate it. I focus on trying to find the minimum viable set of operational restrictions. If a client allows me, I’ll sometimes push the envelope to see how far we can go before we get a kickback or denial. Some manufacturers and waiver filers throw on extra restrictions or equipment requirements. Why not? They aren’t paying for it. They just want a happy customer.

- People like using me as opposed to a waiver application filed by a manufacturer because I can obtain a waiver for multiple drones from different manufacturers. I’m not captive. I don’t care what drones you buy. Want to test out a couple of drones? Let’s file the paperwork for multiple drones so you can see which one you really want to commit to long-term. I also might tell you which drone I think is better.

- I can file a waiver application without you owning a drone. Will one of the drone manufacturers do that?

- I can help you obtain waivers for other waiver operations outside of beyond line of sight (over people, swarming, etc.). Do you have other needs outside of just beyond line of sight? I can help you with those.

- I am more cost-effective when you start combining things or expanding operations as I know the manuals and can add on. This is a big problem people don’t encounter at first but later on because the 2nd application requires the manuals to be amended. That can get really time-consuming if not planned for.

How can we use this waiver as part of an overall low-capital investment strategy? Keep in mind you do NOT need to own the aircraft to obtain the waiver. You could take an asset-light approach by obtaining the waiver and then getting funding such as getting contracts (hopefully with some upfront money to buy the drone).

Can I use other aircraft in the future? If you were approved for a specific make/model, you can purchase as many of those things as you want and fly as many as the waiver will allow. We don’t have the approval tied to specific aircraft serial numbers or registrations. Any make/models not in the waiver will need another waiver application filed and approved.

Besides the Federal Aviation Regulations, what else should we be aware of regarding these drones? Some drones that can fly for more than 30 minutes under certain weather conditions and 60 minutes are export-controlled. See ECCN 9A012.

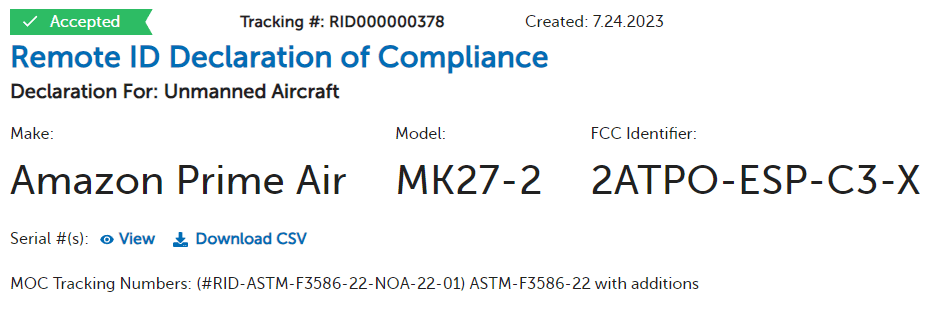

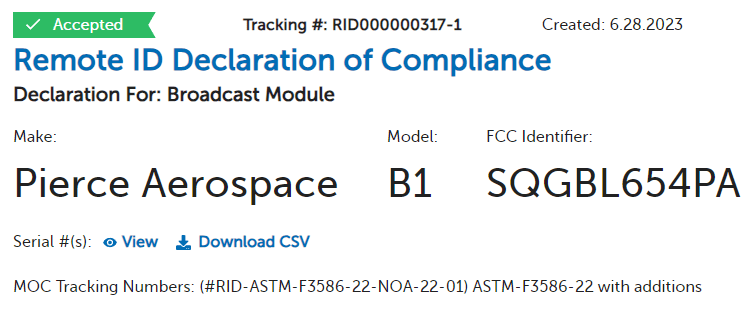

I don’t see my aircraft on that remote ID list. What should I do? Can we file for it? The FAA’s remote identification regulations are law now. The date for operators to comply and have their drones start broadcasting is September 2023. See 14 CFR 89.105. Operators have to either retrofit each aircraft, buy aircraft that can comply with remote ID, or obtain authorization or exemption from the remote ID regulations. Here is the catch for BVLOS, only standard ID aircraft, not broadcast ID, can do BVLOS. If we need to obtain a remote ID COA, that will be an additional cost. There could be a benefit to that in that your drone would be essentially invisible if people were trying to detect the drone to evade security.

Can you help me obtain a drone in a box BVLOS waiver?

Yes, the following information below is for a Part 107 drone in a box BVLOS waiver. Contact me separately for a 91.113 waiver. Here are important points on why you should consider working with me:

- I’m a licensed attorney so the attorney-client privilege applies to our communication. For example, if you messed up really bad, you could tell me that. The attorney-client privilege was designed so you can have a completely open conversation with your attorney. It protects communications. Consultants, drone manufacturers, resellers, employees, and friends are not good people to chat with when you are facing legal issues as they can be compelled to testify against you at trial. They are witnesses.

- I have a malpractice insurance policy that is there to protect you. Think about it. If I mess up by failing to file something, giving you the wrong information, or doing something I should not have done, that insurance policy is there to help make YOU whole.

- People like using me as opposed to a waiver application filed by a manufacturer because I can obtain a waiver for multiple drones from different manufacturers. I’m not captive. Want to test out a couple of drones? Let’s file the paperwork for multiple drones so you can see which one you really want to commit to long-term.

- I can file a waiver application without you owning a drone. Will one of the drone manufacturers do that?

- I can help you obtain waivers for other waiver operations outside of beyond line of sight (over people, swarming, etc.).

- I am more cost-effective when you start combining things or expanding operations as I know the manuals and can add on. This is a big problem people don’t encounter at first but later on.

Here is some info.

PROCESS:

Once I receive the contract and payment, I should be able to file the paperwork in a couple of days to 4 weeks. A lot of this depends on the aircraft, the manufacturer’s documentation, manuals, documentation, etc.

If you are asking for DJI products, chances are I’m going to be very fast.

I’ll ask you to add me to your FAA Drone Zone account (I have instructions to help with this). I’ll log in and file the waiver application. You’ll be able to see everything. If the FAA asks any questions, you’ll see their questions. The FAA will either ask more questions, issue a denial, or issue a waiver.

The overall time from filing to denial or approval will be something like 30-120 calendar days.

GENERAL:

-This is for civil aircraft operations. This is NOT for public aircraft operations. Keep in mind that government entities can choose to fly as civil aircraft.

-This is for under 55-pound aircraft operating under Part 107.

CREW RELATED:

– There will be one certificated remote pilot flying the drone from a location within the United States.

-The pilot will need to file a NOTAM at least 24 hours prior to flight.

AIRCRAFT CRITERIA:

–Must have geofencing.

-Return to Home feature must not allow sUA to deviate from the normal planned flight path

-The aircraft must have a standard remote ID declaration of compliance listed here. https://uasdoc.faa.gov/listDocs A broadcast module will NOT work. 14 CFR 89.115(a)(2)(ii) says that for broadcast module ID aircraft “The person manipulating the flight controls of the unmanned aircraft system must be able to see the unmanned aircraft at all times throughout the operation.” Please find your aircraft and make sure it is standard ID and the serial number is within the range listed. If it is not, email me back so we can discuss it. There is the possibility of obtaining a certificate of authorization if we need a variance from this reg. That will cost extra and will cause extra delays due to the extra FAA approval.

-The sUA must be equipped with high visibility markings and/or anti-collision lighting to increase the conspicuity of the sUA to 1 statute mile for daytime operations.

-Ground control station must display in real-time the following information: sUA altitude, sUA position, sUA direction of flight, and sUAS flight mode, as described in the waiver application. This information must be available at all times to the remote PIC.

-Unmanned aircraft system (ground controller and/or aircraft) must BOTH audibly or visually alert the remote PIC of degraded system performance, sUAS malfunction, or loss of Command and Control (C2) link between the ground control station and the sUA. Note that some control stations might vibrate which provides noise. You make the final call if the vibration is loud enough to be audible.

-The ground control station MUST receive ADS-B signals.

-The ground control must display altitude, position, direction of flight, flight mode, battery life, ADS-B receiving status and C2 status.

-If the aircraft loses link, it must follow a predetermined route to reestablish link or immediately land at a predesignated location.

-All equipment must be in compliance with FCC regulations.

OPERATIONS AREA:

– Ground risk. The operations must be over an area that is sparsely populated or controlled access unless the aircraft can fly over people. If you think the area may be more than sparsely populated, we can discuss it. We may need a 107.39 waiver. It’s best to plan the flight paths over areas where there are no people.

-Air Risk. The operational area can for the entire United States provided you meet the criteria in the waiver manual. In other words, you may be able to fly to most places, but there are certain areas you may need to do more things or be restricted from flying in.

DELIVERABLES:

– Creating Manuals and Concept of Operations Document. I will create an operations manual that also includes normal and emergency procedures. I will also create a training manual that includes one written exam for the remote pilot in command and one written exam for the visual observer. I’ll also create a concept of operations (CONOPs), including a hazard analysis worksheet, and answers to all the Part 107 waiver safety explanation guidelines. It comes out to roughly around 130+ pages of paperwork.

–Answering FAA Questions. If the FAA asks questions, to the best of my ability, I’ll respond free of charge. This includes amending manuals and documents.

–Filing 2nd Application If the First One Is Denied. If there is a denial, I will rework the original request and file it again free of charge. If there are any questions, I’ll work on those as well for free.

FOR THE END GOAL OF:

–One 107.31 waiver.

OPERATION’S CHARACTERISTICS:

–For one location that is sparsely populated or has secure or limited access.

– The drones must be able to complete their entire mission with a certain distance of structures (buildings, towers, antenna, powerlines, etc.) and obstacles (trees). This will vary depending upon the location. Certain areas require you to remain low to the ground (50 ft.) while other areas you can fly higher.

-Daylight only

-For one make and model of aircraft. There isn’t a limit to the number of aircraft but they all must be the same make/model.

– No visual observer.

– The drone operates completely from a box.

-The box has 1 or more cameras that provide enough field of view to preflight the aircraft and the surrounding area sufficiently. 1 or more cameras and lights may need to be installed. Depending on where the box is located, we may need fencing if cameras are not adequate to clear the area.

COSTS:

BVLOS waivers are a pain to obtain, and it’s taken me years to finally dial things in and create the 100+ pages of material. Years of R&D. BVLOS waivers have around a 1-2% success rate. Phrased another way, they have around a 98-99% rejection rate. Here is the data backing up this statement. 2018 – 1% approved (14/1392) See page 5 https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/uas/resources/events_calendar/archive/Submitting-Operational-Waiver-Requests.pdf 2019 1.5% approved (27/1813) Page 29 https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/uas/resources/events_calendar/archive/Is_Your_UAS_Safety_Case_Ready_for_Flight-Leveraging_Research_and_Operations_to_Get_to_YES.pdf

Furthermore, you can go to his link and search for “107.31” to see how many of these waivers are even active. Look at the bottom part of the table and you will see it saying “Showing 1 of XXX of XXX entries.” https://www.faa.gov/uas/commercial_operators/part_107_waivers/waivers_issued/

The following prices are if you sign MY contract. These prices are good for the next 30 calendar days after you receive this email.

For one BVLOS waiver for one drone make/model and one make/model of box, I’ll charge a flat rate of 5,000.

If you want multiple aircraft or other regulations waived, email me and I’ll come back with a fixed price

FAQs

Why you and not someone else? I heard someone else can do the waiver.

There are multiple other people and sellers out there offering BVLOS waiver filing services. Here are some of their limitations:

-Some of these entities have a template created by the manufacturer that is static. It doesn’t change with time. I’m constantly updating and pushing the boundaries to have the least restrictive conditions possible. This translates into lower operating costs or more areas to service.

-The restrictions others propose for you are overly restrictive. The manufacturer or seller was just focusing on getting you an approval. You want the least amount of restrictions possible.

-Some of these entities sell you additional hardware and services for mitigating air risk. One thing I’ve seen multiple times is that people getting sold some expensive system that deals with detecting unmanned aircraft. I have never used one of these for my waivers. My waivers have a lower capital expenditure than others.

What are your benefits compared to the other waiver filers or sellers with a manufacturer template?

-My waivers have fewer restrictions than others. For example, many will limit the shielding to 50ft. above the ground. I ask for more. Some will do only shielding, I do shielding or VO ops which give you the flexibility to do different things.

-I can do multiple aircraft (DJI Mavic 3, DJI Matrice 350, etc.) so they can all fly BVLOS.

-I’m not captive to a particular manufacturer. If you have other aircraft from another manufacturer, I can try and put everything on one waiver.

-I can provide clients advice on all sorts of other area such as export law, economic authority regulations, and various federal statutes.

-I have insurance.

-Attorney-client privilege applies to our communication.

-If you crash, we already have a relationship.

Are there any other benefits to this waiver? Yes, (1) use it for marketing because they are pretty rare, and (2) to go and enter into contracts with companies.

How can we use this waiver as part of an overall low-capital investment strategy? Keep in mind you do NOT need to own the aircraft to obtain the waiver. You could take an asset-light approach by obtaining the waiver and then getting funding such as getting contracts (hopefully with some upfront money to buy the drone).

Can I use other aircraft in the future? If you were approved for a specific make/model, you can purchase as many of those things as you want and fly as many as the waiver will allow. We don’t have the approval tied to specific aircraft serial numbers or registrations. Future aircraft will need another waiver application filed and approved.

Besides the Federal Aviation Regulations, what else should we be aware of regarding these drones? Some drones that can fly for more than 30 minutes under certain weather conditions and 60 minutes are export controlled. See ECCN 9A012.

I don’t see my aircraft on that remote ID list. What should I do? Can we file for it? The FAA’s remote identification regulations are law now. The date for operators to comply and have their drones start broadcasting is September 2023. See 14 CFR 89.105. Operators have to either retrofit each aircraft, buy aircraft that can comply with remote ID, or obtain authorization or exemption from the remote ID regulations. Here is the catch for BVLOS, only standard ID aircraft, not broadcast ID, can do BVLOS. If we need to obtain a remote ID COA, that will be an additional cost. There could be a benefit to that in that your drone would be essentially invisible if people were trying to detect the drone to evade security.

Why should we pick you? (1) I’m a licensed attorney so the attorney-client privilege applies to our communication. For example, if you messed up really bad, you could tell me that. The attorney-client privilege was designed so you can have a completely open conversation with your attorney. Consultants, drone manufacturers, resellers, employees, and friends are not good people to chat with when you are facing legal issues. Anything you say can be used against you. (2) I have a malpractice insurance policy that is there to protect you. Think about it. If I mess up by failing to file something, giving you the wrong information, or doing something I should not have done, that insurance policy is there to help make YOU whole.

I’m also not captive to one manufacturer. I can help clients obtain approvals for different makes and models of aircraft.

What if you mess up? I have malpractice insurance for 1 million dollars.

How do I know you aren’t going to just take the money and run? Great question. Unlike most people in the drone industry, my conduct as an attorney is regulated. Here is my Florida Bar profile showing no disciplinary history and that I’m a member in good standing. https://www.floridabar.org/directories/find-mbr/profile/?num=109249 If I stiff you or act in a bad way to you, call the Florida Bar. They can then come after me and in the worse scenario, disbar me. I have skin in the game. My law license is your security.

Can I talk to one of your previous clients? My clients don’t want me handing their info out and it’s all confidential anyways. However, you can see on my Google Business Page the reviews left for me. No, I didn’t pay for any of them. You can also go over to regulations.gov and search the public dockets for clients I have filed exemptions for.

Have you been disciplined by the Florida Bar? Nope. You can verify this. Go to my Florida Bar page and see that it says I don’t have a discipline record.

How Do We Get Started?

Let me know and I’ll send you my contract.

Comparison of My Services to Others

Insurance

- Rupprecht Law. I have a $1 million policy

- Skydio – ?

- Censys – ?

Provide legal advice

- Rupprecht Law – I can provide legal advice because I’m a licensed attorney

- Skydio – They are not a law firm and cannot provide legal advice. See this article for more discussion.

- Censys – They are not a law firm and cannot provide legal advice.

Attorney-Client Privileged Communications

- Rupprecht Law – Yes

- Skydio – No

- Censys – No

Pilot Certificate

- Rupprecht Law – Flight Instructor (CFI/CFII), Commercial Pilot, Certificate, and Remote Pilot

- Skydio – Jen Player is a Private Pilot and Remote Pilot. Jakee Stoltz is a Flight Instructor and Commercial Pilot.

- Censys – ?

What aircraft?

- Rupprecht Law – I can work with any manufacturer. I’m not captive. I work with whatever aircraft you want now or in the future.

- Skydio – Skydio aircraft.

- Censys – ?

Area of Knowledge

- Rupprecht Law – I can help with a wide variety of waiver, exemption, and authorization issues. I’ve done over people, BVLOS, moving boat, swarming, over 400 waivers and hundreds of exemptions for crop dusting and closed set cinematography for a wide area of industries. I’ve done COAs for remote ID to many different types of airspace.

- Skydio – Jen Player has experience in doing BVLOS waivers.

- Censys – Rob has experience in doing BVLOS waivers.

Can You Have A Fully Autonomous Drone In A Box Solution?

Most people think you can just fully automate your inspections where no person has to be in the loop. That doesn’t work because the law doesn’t allow it. The law was set up to have people obtain airmen certificates to be pilots in command. There is no legal mechanism to have software ALONE be the airmen and pilot in command.

Creating some “software” to be an “airman” under the law creates a massive set of issues because who or what is responsible for the operations? The software? Who is responsible for the software? How does the FAA even validate that software or weave that into its framework of how the FAA manages safety?

Yes, we can heavily automate everything to decrease pilot workload but at the end of the day, it’s a pilot supervising those automations.

If you are concerned about keeping your operating costs low, find a drone in a box solution that is heavily automated and use one remote pilot managing 5+ drones simultaneously. You will have to obtain a 107.35 waiver for this if it is done under Part 107. That’s how you drive down operating costs. One pilot managing multiple drones operating sequentially or in parallel.

Things To Consider When Purchasing A Drone In A Box Solution

1. OpEx and CapEx Out-the-Door Numbers

You need to figure out the final out-the-door capital expenditure (CapEx). Here are some questions you need to answer.

- Does the manufacturer charge a subscription for the software?

- What will the concrete pad cost?

- What will the electrician cost?

- What will the legal approvals cost?

- What is the main air risk mitigator? Is it a radar system? Casia G system? A human visual observer searching the sky? What are those training, installation, and ongoing subscription costs?

- Does a parachute need to be installed because you will be flying over people? What will that cost? Will integrating that parachute to be remotely deployed cost any extra?

- Is this aircraft export-controlled? If so, you’ll need to protect it and comply with the export laws that speak to how technical data is transferred, who can have access to the aircraft, etc.

2. What Aircraft Can Be Used For This Box?

Some of the box companies make boxes that can be compatible with different aircraft. The Hextronics Universal box works with the DJI Mavic 2 series, DJI Mavic 3 series, Parrot Anafi USA, and Parrot Anafi Ai. You may already own aircraft in your fleet (DJI Matrice 300 for example) and wish to just purchase boxes for an already existing fleet. This results in a lower CapEx. Try and figure out how to use what you already have.

3. Can I Have A Fixed Wing Drone In A Box?

Yes. There is one company I have seen do this with a fixed-wing electric vertical takeoff and landing (EVTOL) design. Connect that with a good communications system. Boom you have a drone that can do 60-90 minutes of flying at great ranges. The only problem is going to be figuring out air risk.

4. Can It Swap Out Batteries And Sensors?

The Airrow box can swap out batteries and also payloads. Here is a video. This can be beneficial in certain markets such as the Oil and Gas industry where a company may want a drone to use a camera and also a methane sniffer.

5. Will The Box Be Future Proof?

Find out if the manufacturer is planning on trying to keep the box static and just upgrade certain parts as new aircraft or if the box is built for specific aircraft already built. Otherwise, you might have to budget more money later on to purchase another box whenever a new aircraft is acquired.

6. Are There Enough Sensors to Preflight The Area?

- 107.15(a)- “No person may operate a civil small unmanned aircraft system unless it is in a condition for safe operation. Prior to each flight, the remote pilot in command must check the small unmanned aircraft system to determine whether it is in a condition for safe operation.”

- 107.49 – “Prior to flight, the remote pilot in command must: (a) Assess the operating environment, considering risks to persons and property in the immediate vicinity both on the surface and in the air. This assessment must include: (1) Local weather conditions; (2) Local airspace and any flight restrictions; (3) The location of persons and property on the surface; and (4) Other ground hazards. . . (c) Ensure that all control links between ground control station and the small unmanned aircraft are working properly; (d) If the small unmanned aircraft is powered, ensure that there is enough available power for the small unmanned aircraft system to operate for the intended operational time;[.]”

7. How Accurate Is Its GPS Vertical Accuracy?

This becomes an important point when you are trying to keep your operating costs low. If you want to get away from the visual observer on site, then you need to figure out how to keep the drone close enough to infrastructure or obstacles. This becomes an issue if your vertical accuracy is not that great and you have to keep a certain distance from the tops of trees.

8. Can It Fly Over People or Moving Vehicles?

When you think of beyond line of sight waivers, you think of air risk. Yes, but if you fly beyond the line of sight, how do you maintain compliance with the regulations telling you to NOT fly over people? This is why I tell people there is a hidden 107.39 and 107.145 discussion in every 107.31 waiver application.

Sure you can say it’s closed access or extremely remote (rural powerlines and solar farms). That fixes things in those scenarios. But what about where there are people such as construction sites?

Roads also become an issue. You end up having to play Frogger.

Does your aircraft have an operations over people (OOP) declaration of compliance? I have an entire article on FAA Declarations of Compliance. Are there any after-market parachutes that will work? Can that be deployed remotely? Parachutes on top of aircraft could cause issues for box clearance. Is the box tall enough? Will the box be tall enough in the future for future aircraft and parachute systems?

9. Does It Have Standard Remote ID?

All drones that must be registered must have remote ID. There are only two types of remote ID: broadcast module or standard ID. Only standard ID can do BVLOS. See 14 CFR 89.115(a)(2)(ii). Before purchasing a drone, make sure the aircraft has a Declaration of Compliance from the FAA for standard remote ID. Do not just take the word of a salesman. I have seen this issue over and over again. Find the Declaration of Compliance @ https://uasdoc.faa.gov/listDocs and read it carefully. If you can’t find it, ask the manufacturer for it. If you don’t see it in the database, it does NOT have a compliant remote ID solution. This is important as many are saying they have a remote ID aircraft but in reality, the remote ID is not approved by the FAA. I have an entire article on FAA Declarations of Compliance. If your solution isn’t compliant, you can obtain a Part 89 certificate of authorization or exemption to fix this. Contact me if you need help with this.

10. Can It Stand Up To The Weather?

Some boxes are not airtight. Is the environment you are using it going to have dust, water, and high or low temperatures? Will the box need to be airtight? If so, will that require it to be air-conditioned somehow? What is the flight time in extreme weather? LIPO batteries stink in cold weather. Do you have enough flight time when the batteries are around 20F?

12. Does The Drone Receive ADS-B Signals?

This is non-negotiable for drone in a box where you want to use the “shielded” type of operations and not have a visual observer on-site managing deconfliction of the airspace.

13. Does The Ground Control Station Have Audible And Visual Alerts?

Does the ground station provide audible and visual alerts of “degraded system performance, sUAS malfunction, or loss of Command and Control (C2) link between the ground control station and the sUA[?]” This is an important point. There are 6 alerts you are trying to find out about here. Most manufacturers will say they have “alerts” but do they have visual and audible alerts of all three of those areas?

14. Does the ground control station display enough telemetry?

Control station must display in real-time the following information: sUAaltitude, sUA position, sUA direction of flight, and sUAS flight mode.

15. How Well Does It Communicate At Our Proposed Ranges?

This is an important point. Certain radio frequencies are not that great low to the ground when you go farther out. If you are trying to do “shielded” ops where you fly close to trees or structures, this becomes very important. Certain environmental conditions can also really degrade system performance (e.g. Georgia pine trees). See my Fresnel Calculator to get an idea of why this is an issue. To ground truth this, obtain a BVLOS waiver and fly the drone out at those ranges. See if the radio’s RSSI drops off.

16. How can the radio frequency transmitter be configured?

Is the transmitter on the ground or can you have a pole you can transmit from that will provide a greater radio line of sight? Certain environmental conditions and radio frequencies don’t work well at ranges (see my Fresnel zone calculator to get an idea) so you would need to put the transmitter on a pole to have a greater RF range. In relation to this, how are the antennae oriented for the operations? Antennas have radiating patterns so you would want to install the box in a way that allows the appropriate coverage and there are no dead spots. Does your controller have two or more antennas in different orientations with overlapping coverage?

Drone In A Box Companies

As you go through these, some make aircraft and boxes, some software, some just boxes, and some provide a service.

- RocketDNA

- Hextronics

- Icaros

- Nightingale

- DJI

- Heisha

- Autel

- American Robotics

- Easy Aerial

- Flytbase

- Sunflower Labs

- Hive

- Percepto

- Volatus

- Asylon Robotics

- Hoverfly

- Drone Hub

- Airrow Team

- Axon Air

- Strix

- JOUAV has a fixed wing box.

- Sphere Drones

Conclusion

I wrote this article myself. I didn’t outsource it. I have a lot of information in my head (that was not in this article) and can do things faster than most. Time is money. Can you afford to not hire me? Contact me.

The FAA also “regulates” in multiple ways by creating advisory circulars, or memos or interpretations on the regulations. Regulations ARE the law while advisory circulars, memos, and interpretations are the FAA’s opinion of how to follow the law, but they are NOT the law. However, they somewhat become law in effect because even though they are not law, the interpretations change people’s behavior who would rather not pay an attorney to defend them in a prosecution case. They in effect stay out of the grey area like the guy with the yellow shirt in the graphic. When I say grey, I don’t mean that it is not clear as to whether it is law, the grey area is not law, but I mean that it is unclear as to whether a judge would agree with the FAA’s opinion and would find the guy in the yellow shirt to be in violation of the regulations. In short, the law is what you get charged with violating, but the interpretations/memos/advisory circulars are what determine if you are on the FAA “hit list” so they can go fishing to try and get you with the law.

The FAA also “regulates” in multiple ways by creating advisory circulars, or memos or interpretations on the regulations. Regulations ARE the law while advisory circulars, memos, and interpretations are the FAA’s opinion of how to follow the law, but they are NOT the law. However, they somewhat become law in effect because even though they are not law, the interpretations change people’s behavior who would rather not pay an attorney to defend them in a prosecution case. They in effect stay out of the grey area like the guy with the yellow shirt in the graphic. When I say grey, I don’t mean that it is not clear as to whether it is law, the grey area is not law, but I mean that it is unclear as to whether a judge would agree with the FAA’s opinion and would find the guy in the yellow shirt to be in violation of the regulations. In short, the law is what you get charged with violating, but the interpretations/memos/advisory circulars are what determine if you are on the FAA “hit list” so they can go fishing to try and get you with the law.