A common issue many people face is comparing the Section 44807 exemption vs. Part 107. On top of that, depending on if you are recreational or government, this throws extra additional problems into the mix.

There are so many choices and making the wrong choice does have consequences in that your operations could unnecessarily be limited.

Don’t you wish someone put them all into an easy-to-figure-out table?

Look no further because you are in the right place.

Let’s start clearing things up.

There is much confusion on this issue because of the different terms, their locations in the law, and the reasons why the different methods of getting a drone airborne legally were created. You need to think of each of these different methods of getting airborne like it was a tool. Each tool was designed to fix certain problems at a certain point in time. Some people can have more than one tool. Wisdom is to know when to use which tool for the job.

Keep in mind that the different methods listed below are only SOME of the methods. I picked the most popular methods of getting airborne legally but there are other alternatives to the ones listed.

Please keep in mind that this article is designed to compare and contrast SOME of the major provisions and is NOT an exhaustive study of all the issues. In other words, you should not rely on this article for legal advice because there are many issues in play. This is for educational purposes only.

Table of Contents of Article

Table Comparing Aircraft, Pilot, Airspace, and Operational Requirements

Please keep in mind these are the major points and not ALL of the points in contrast. If I put everything down, the table would get messy and hard to read.

|

Aircraft Requirements |

Pilot Requirements |

Airspace Requirements |

Types of Operations |

| Part 107 |

Under 55 lbs only. |

Remote Pilot Certificate with SUAS Rating |

Class G, unless authorized or waived. See 107.41. |

Day & night, visual line of sight, 400ft AGL(unless within 400ft of a structure), not over people, etc. |

| Section 44807 (Formerly Section 333) |

As Required in the Exemption |

Part 61 Certificate or a Remote Pilot Certificate with the exemption. Driver’s license or 3rd class medical. |

Most exemptions say to follow the “Blanket COA” which comes with the exemption. It has airspace restrictions. |

As defined by the exemption. Typically over 55lb+. Can be beyond line of sight or under 55 pounds. |

| Special Airworthiness Certificate (Experimental Category) |

Experimental Special Airworthiness Certificate. |

Part 61 Certificate (Sport, Recreational, Private, Commercial, ATP, but not Student). |

Follow the terms of the SAC. |

R&D, Showing Compliance with Regulations, Crew Training, Exhibition, Air Racing, Market Surveys. See Section 21.191. |

| Special Airworthiness Certificate (Restricted Category) |

Previously type certificated or manufactured & accepted by an Armed Force of the United States. |

Part 61 Certificate (Sport, Recreational, Private, Commercial, ATP, but not Student). |

Follow the terms of the SAC. |

Agriculture, forest and wildlife conservation, aerial surveying patrolling, weather control, aerial advertising, or any other operation specified by the FAA. See Section 21.25. |

| Standard Airworthiness Certificate (21.17(b) Process) |

Will have all sorts of restrictions. May need extra exemptions and waivers to fix regulatory problems. It is not a complete fix. |

| Public “Blanket” COA (Version 1.2) |

Under 55lbs public aircraft only. |

Self-Certify |

Class G & at or below 400ft AGL. Beyond 5/3/2 airport distance requirements. |

Section 40102(a)(41) & 40125(a)(2) and within public “blanket” COA limitations. |

| Public COA |

Public aircraft only. |

Self-Certify |

Self-Certify |

49 USC §§ 40102(a)(41); 40125 |

Part 107

This part of the regulations went into effect on August 29, 2016. Prior to 107, we were operating predominately under a Section 333 exemptions (now called a 44807 exemption).

For many, Part 107 is the best solution; however, there are particular operations that cannot be done under just Part 107 or a Part 107 waiver such as over 55-pound and heavier operations, crop dusting operations, beyond visual line of sight property transport or moving vehicle in a congested area property transport, etc. If you are needing help with any of those, contact me.

For operations, that cannot be completed under Part 107, a Section 44807 exemption could be a good alternative, but not always the best. The idea I want to take away is that there are different tools for different problems. Some operators can have multiple tools in their toolbox to accomplish their missions depending on the particular facts. For example, a fire department could have 107 remote pilots, a Section 44807 exemption, and a public COA all at the same time. The problem at hand determines which tool you would pull out of the toolbox.

Section 44807 Exemption (Formerly Called a Section 333 Exemption)

This basically is a legal Frankenstein created using the FAA’s authority given in 49 USC Section 44807, Part 11’s exemption process, and the Part 91 waiver process. The first exemptions came out in September 2014 and were the backbone of the commercial drone industry till Part 107 came out which had far less restrictive requirements.

From September 2014 -November 2016, we saw multiple versions of the exemptions which morphed and changed over time. For example, the early exemptions had restrictions requiring the pilot to keep a 25% battery reserve, it then changed to 30%, and then a 5 minute reserve which goofed over the cinematographers who originally worked with the FAA to craft the exemptions! Why did it hurt cinematographers? Because if their large heavy lift drones had a flight time of 15 minutes, under the original exemptions they would be required to keep a 25% battery reserve (3.75 minutes) while under the newer restrictions it is 5 minutes which results in a loss of available flight time.

In November 2016, the FAA unilaterally updated over 5,000 to all have the same set of restrictions. One wonders how that was not arbitrary and capricious.

The two most problematic restrictions for the exemption operators were the 500ft “bubble” around the drone which non-participating people and property must stay out of and the requirement to operate under a certificate of authorization.

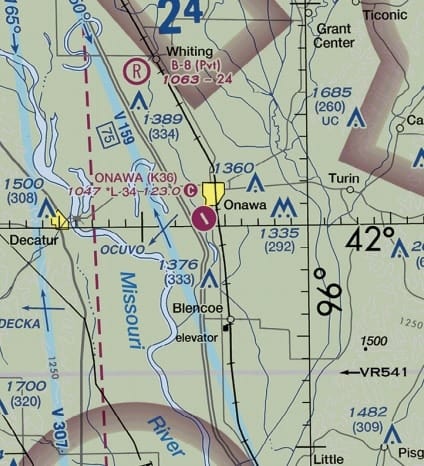

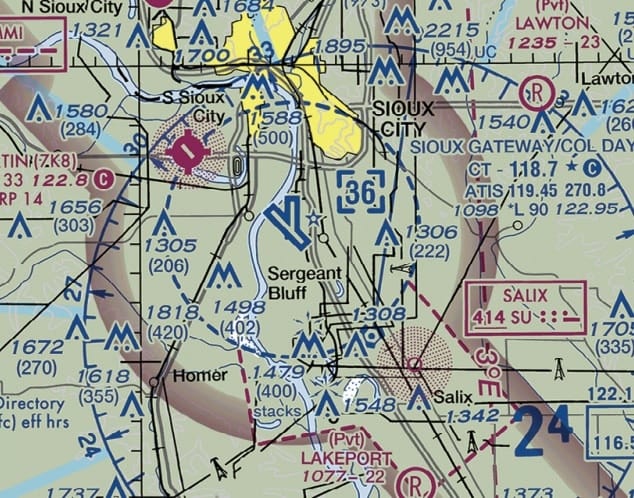

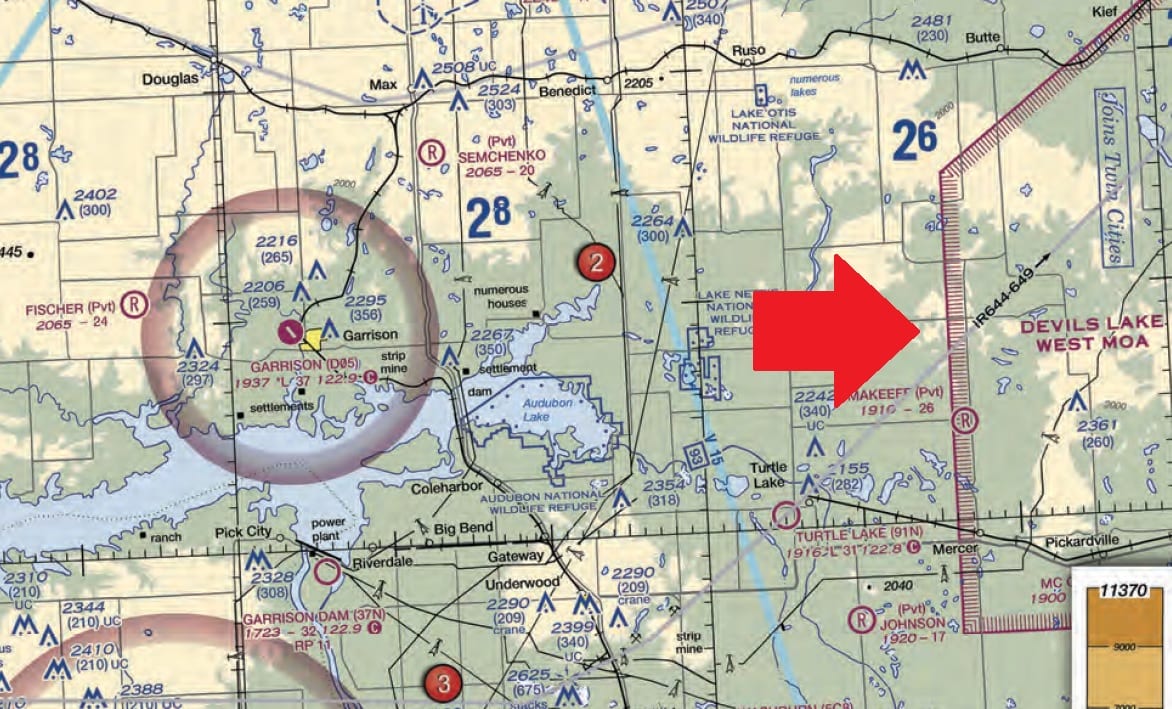

Early on, the exemptions did not come with COAs and people had to apply for them. The FAA quickly learned the error of that and created the “blanket” COA which was issued to all the exemption holders upon approval. The FAA updated the “blanket” COA over time from 200ft AGL to 400ft AGL. But here is the problem why the certificate of authorization was the second biggest problem, the “blanket” COA is good for operations outside of 5 NM from a towered airport, 3NM from an airport with an instrument approach procedure, or 2NM from an airport, heliport, glider port, etc. This made operations in cities or near them almost impossible because you would have to apply for a new COA, because the “blanket” COA would not work. People could not obtain a COA in time. The jobs would go to the illegal operators.

The FESSA of 2016 extended the powers to night and beyond the line of sight flying.

The FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 officially codified the provision into 49 USC Section 44807. These are still being issued but much more rarely. They are for 55-pound and heavier aircraft. The aircraft that need exemptions without any airworthiness issues just do a straight Part 11 exemption (like crop spraying drones flying under Part 107 carrying hazmat which is prohibited by 107).

Airworthiness Certificates

The FAA has been charged with maintaining the safety of the national airspace system and protecting people on the ground. One of the ways the FAA ensures safety is by certifying the aircraft to make sure it is airworthy (it won’t fall out of the sky and kill people). This process which was originally designed for manned aircraft has been used for unmanned aircraft successfully.

There are two types of airworthiness certificates: (1) standard and (2) special.

There has been at least one standard type certificate issued for an unmanned aircraft, two special airworthiness certificates in the restricted category, and multiple special airworthiness certificates in the experimental category.

Obtaining an airworthiness certificate is time-consuming. A major reason it is rarely used today is an operator could just go the Section 44807 exemption route or the Part 107 route. However, there are some instances where a special airworthiness certificate could be more beneficial than the 44807 exemption or Part 107. It just depends on the facts of the intended operations. Different tools in the toolbox.

One point to mention is that an unmanned aircraft would not just need an airworthiness certificate but may also need additional approvals (exemptions and/or waivers) to be in compliance with the regulations.

Public COA

This method is only available for government agencies. The agency has to be fulfilling certain specific governmental functions under certain conditions for the operator to get the ability to self-certify their own pilot, aircraft, maintenance, and medical standards. The FAA is very strict on the missions and requirements because it does not want government agencies to run commercial types of missions or non-government missions under a public COA which is far less restrictive than other methods.

A government operator obtains a public COA by first sending the FAA a declaration letter outlining the agency and its intended missions fall within the public aircraft statutes, the FAA reviews the declaration letter to determine if it is sufficient, the FAA gives the agency access to the COA portal to file a COA application, the government agency files the COA application, the FAA reviews the COA application and either approves, denies, or asks for more information. The agency then operates under the public COA and the Federal Aviation Regulations.

When the exemption method was getting into full swing, public aircraft operators noticed that the exemption process seemed quicker and the “blanket” COAs that were being given out were for the entire United States, except for certain areas, while the public COAs were mission, aircraft, and location specific. This was a no-brainer so government agencies started obtaining exemptions because they were less restrictive than the public COAs.

Other government agencies were upset and wanted a similar deal to the exemption’s blanket COA so the FAA created the “blanket” public COA which is basically a frankensteined version of a public COA, an exemption, and the blanket COA.

Agencies were happy for a while but caught on that the exemptions were evolving to be less restrictive while the blanket public COA stayed the same. For example, the blanket public COA requires the pilot to have a private, commercial, or ATP certificate to operate near certain types of airports while the exemptions required as little as a sport certificate. Additionally, when Part 107 came out, the public blanket COAs still said that the pilot had to have passed the private pilot knowledge exam to fly in most of Class G airspace while a government operator could have their pilots obtain a remote pilot certificate by passing a remote pilot knowledge exam which is easier than a private pilot knowledge exam!

This is why few government agencies today go for a public COA or public blanket COA; however, there are sometimes when a public COA is the best solution for the mission but that is fact specific. Different tools for different problems.

Conclusion

I outlined a brief summation of some of the major points above. There are all sorts of little contrasts between each of the different methods. If you are needing help with obtaining a tool to put in your toolbox (waiver, authorization, exemption, public COA, etc.), contact me.

Paying for 30 minutes of my time can save you lots and lots of headaches, time, and money. We can outline a game plan for your operations in 30 minutes so you can stop wasting time reading and focus on achieving your goals of operating a drone to save time, money, or lives.

Stop wasting time and contact me to schedule a phone call. :)

If you are interested in learning more, I have put below:

Example of a New 44807 Exemption

Example of an Older 333 Exemption

Example of a Blanket COA

Example of a Public “Blanket” COA (Version 1.0)

Example of a Public “Blanket” COA (Version 1.2)

Example of a New 44807 Exemption

Conditions and Limitations

In this grant of exemption, Victor Lee & Associates Inc. is hereinafter referred to as the operator:

1. Operations authorized by this exemption are limited to Shotover U1 conducted by Victor Lee and are limited to the operations described in the petition for exemption and the operating documents. The aircraft’s maximum takeoff weight must not exceed 88 lbs. Proposed operations of any other UAS requires a new petition or a petition to amend this decision.

2. The operator must petition for an amendment to this decision if the operator makes any update or revision to the operating documents, aircraft systems, operating parameters, or other supporting documents that would affect the basis upon which the FAA granted this exemption. The documents on which the FAA relied for granting this petition for exemption are listed above, within the section titled, “Petitioner supports its request with the following information.”

3. Air Traffic Organization (ATO) Certificate of Waiver or Authorization (COA). All operations that occur pursuant to this exemption must be conducted in accordance with an ATO-issued COA. The exemption holder must apply for a new or amended COA if it intends to conduct operations that the terms of the COA do not permit. If a conflict between the COA and this condition exists, the more restrictive provision will apply. In the absence of any express altitude restriction in a COA or any other document the FAA provides that applies to operations under this exemption, the maximum altitude shall be 400 feet above ground level (AGL). Altitude must be reported in feet AGL.

4. The UA must be operated within visual line of sight (VLOS) of the PIC at all times. This requires the PIC to be able to use human vision unaided by any device other than corrective lenses, as specified on the PIC’s FAA-issued airman medical certificate or U.S. driver’s license.

5. All operations must utilize a visual observer (VO). The VO and PIC must be able to communicate orally at all times; electronic messaging or texting is not permitted during flight operations. The PIC must ensure that the VO can perform the duties required of the VO.

6. This exemption does not excuse petitioner from complying with 14 CFR part 375. If operations under this exemption involve the use of foreign civil aircraft, the operator must obtain a Foreign Aircraft Permit pursuant to 14 CFR § 375.41 prior to conducting any commercial air operations under the authority of this exemption. Application instructions are specified in 14 CFR § 375.43.

7. The PIC must be designated before the flight and cannot transfer his or her designation for the duration of the flight. In all situations, the PIC is responsible for the safety of the operation. The PIC is also responsible for meeting all applicable conditions and limitations as prescribed in this exemption and ATO-issued COA, when conducting operations, and operating in accordance with the operating documents.

8. PIC certification. Under this exemption, a PIC must hold at least a Private, Sport, or Recreational Pilot Certificate with a current FAA medical certificate or current U.S. driver’s license issued by a state, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, a territory, a possession, or the Federal government. The PIC must also meet the flight review requirements specified in 14 CFR § 61.56 in an aircraft in which the PIC is rated on his or her pilot certificate.

9. PIC qualifications. The PIC must be qualified in accordance with operator and OEM training programs and manuals to operate the Shotover U1 safely and in a manner consistent with how it will be operated under this exemption. The PIC, therefore, must make evasive and emergency maneuvers, and maintain appropriate distances from persons, vessels, vehicles and structures before operating non-training, proficiency, or experience-building flights under this exemption. PICs must remain current and qualified before conducting operations under this exemption. Moreover, PICs must immediately inform the petitioner of any deviations or exemptions they obtain that might affect their compliance with the PIC requirements under this exemption.

10. Prior to each flight, the PIC must conduct a pre-flight inspection, become familiar with all information concerning that flight, pursuant to 14 CFR § 91.103, and determine the UAS is in a condition for safe operation. The pre-flight inspection must account for all potential discrepancies, e.g., inoperable components, items, or equipment. The UA may not operate if the inspection reveals a condition that affects the safe operation of the UAS, until the PIC determines the UAS is in a condition for safe flight.

11. The PIC is prohibited from beginning a flight unless, considering wind and forecast weather conditions, there is enough available fuel for the UA to conduct the intended operation with sufficient reserves such that the PIC can land the UA without posing an undue risk to aircraft or people and property on the ground, o rthe reserve fuel recommended by the manufacturer, if greater, is satisifed.

12. All crewmembers, including PIC and ground personnel used for takeoff and landing, must maintain two-way voice communications with each other during operations. If unable to maintain two-way voice communication, the PIC will land the UA in a safe location as soon as the PIC determines it is practicable to do so. For the purpose of compliance with all conditions and limitations in this exemption, the term “crew member” includes the PIC, the person manipulating the controls, the visual observers (VO), Camera Operator, and a Telemetry Operator and any other personnel required for the safety of the flight operation.

13. No required crewmember may engage in electronic messaging, texting, or other communication using any personal electronic device during flight operations which could distract any crewmember from the performance of his or her duties or which could interfere in any way with the proper conduct of those duties.

14. Each UA must be controlled by only a single control station and one PIC at a time. A PIC may not operate multiple UA at the same time.

15. All operations must be conducted under visual meteorological conditions (VMC). Flights under special visual flight rules (SVFR) are not authorized.

a. The PIC must obtain and use real-time weather information as described in the operating documents.

b. Each operation may only occur when weather in the area of the operation is reported and forecast to be at least 1,000-foot ceiling and 3 statute mile visibility within 1 hour before and 1 hour after takeoff and landing.

c. The PIC must land the Shotover U1 as soon as possible if the PIC is unable to comply with the required ceiling and visibility requirements.

16. Operations under this exemption may not be conducted during night, as defined in 14 CFR § 1.1.

17. The distance between the ground control station and the Shotover U1 must not exceed radio line of sight through the entirety of the proposed flight path during all operations. Operations using multiple ground control stations and/or command and control link relays along the flight path for handoff between ground control stations are prohibited.

18. Any maintenance or alterations that affect the operation of the Shotover U1 or its flight characteristics, such as replacement of a flight critical component, must undergo a functional test flight prior to conducting further operations under this exemption. Functional test flights must be conducted within VLOS by a PIC with the assistance of a VO, and other personnel required to conduct the functional flight test (such as a mechanic or technician) and must remain at least 500 feet from all other people. The functional test flight must be conducted in such a manner to not pose an undue hazard to persons and property. The petitioner must permit the Administrator to observe functional test flights upon the request.

19. The operator must follow the OEM’s operating limitations, maintenance, service bulletins, overhaul, replacement, inspection, and life limit requirements for the Shotover U1 and its components. Each UAS operated under this exemption must comply with all OEM safety bulletins.

20. A copy of the Victor Lee Flight Operations Manual, Aircraft Maintenance Manual/Service Manual, FCC Grant of Equipment Authorization, and a copy of this Manual/Service Manual, FCC Grant of Equipment Authorization, and a copy of this exemption must be accessible to the PIC at the control station during all operations that occur under this exemption, and made available to the Administrator upon request. If a discrepancy exists between the conditions and limitations in this exemption and the procedures outlined in the aforementioned documents, the conditions and limitations herein take precedence and must be followed. Otherwise, the petitioner must follow the procedures as outlined in its operating documents. The petitioner may update or revise its operating documents. The petitioner must track such revisions and present updated and revised documents to the Administrator or any law enforcement official upon request. If the petitioner determines that any update or revision would affect the bases upon which the FAA granted this exemption, then the petitioner must petition for an amendment to its grant of exemption. In this regard, this document describes all such bases. The petitioner must also present updated and revised documents if it petitions for extension or amendment to this grant of exemption. The petitioner must submit such updates by contacting the FAA’s Flight Standards Service, General Aviation and Commercial Division.

21. All flight operations must be conducted at least 500 feet from all persons who are not directly participating in the operation, and from vessels, vehicles, and structures, unless when operating:

a. Over or near people directly participating in the operation. People directly participating in the operation of the Shotover U1 include the PIC, crewmembers, and other consenting personnel whose presence is necessary to ensure the safety of the operation.

b. Near nonparticipating persons. The Shotover U1 may be operated closer than 500 feet to a person who is not directly participating in the operation only when barriers or structures are present. Such barriers must sufficiently protect the person from the aircraft and from debris or hazardous materials from the aircraft. Under these conditions, the petitioner must ensure the person remains under such protection for the duration of the operation. If a situation arises in which the person leaves such protection and is within 500 feet of the Shotover U1, flight operations must cease immediately in a manner that does not cause undue hazard to any person.

c. Near vessels, vehicles and structures. Prior to conducting operations within 500 feet of any vessels, vehicles, or structures, the petitioner must obtain permission to proceed within 500 feet from a person with authority over such vessels, vehicles or structures. The PIC must first assess the risk of operating closer to those objects and determine that it does not present an undue hazard.

22. The UA may not be operated less than 500 feet below or less than 2,000 feet horizontally from a cloud or when visibility is less than 3 statute miles from the PIC.

23. The UA must remain clear and give way to all manned aviation operations and activities at all times.

24. Operations under this exemption may not occur from any moving vehicle or aircraft.

25. Frequency spectrum approval is independent of this grant of exemption and the FAA COA process. The FAA encourages the operator to remain aware of all relevant requirements of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), especially those concerning frequency spectrum use. Please see the appropriate provisions of title 47, Code of Federal Regulations.

26. The PIC may not begin or continue a flight if any GPS outage, signal fault, integrity issue, NOTAM in effect for any part of the planned operational area, or any other condition affects the functionality or validity of the GPS signal.

27. The PIC must abort the flight operation if circumstances or emergencies arise that could degrade the safety of persons or property. In such cases, the PIC’s termination of flight operations must not cause undue hazard to persons or property.

28. Accidents must be reported to the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) per instructions contained on the NTSB Web site: www.ntsb.gov.

29. All training operations must be conducted during dedicated training sessions. Training to conduct operations with the Shotover U1 must not occur adjacent to neighborhoods, or near or over people.

30. This exemption is not valid for operations outside of the United States.

Unless otherwise specified in this exemption, the UAS, the UAS PIC, and the UAS operations must comply with all applicable parts of 14 CFR including, but not limited to, parts 45, 47, 61, and 91.

Example of an Older 333 Exemption

Dear Section 333 Exemption Holder:

This letter is to inform you that we are amending your exemption that authorizes unmanned aircraft operations under Section 333.1 It explains the basis for our decision, describes its effect, and lists the revised Conditions and Limitations.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has determined that good cause exists for not publishing a summary of the petition in the Federal Register because this amendment to the exemption would not set a precedent, and any delay in acting on this petition would be detrimental to the petitioner. The unmanned aircraft authorized in the original grant are comparable in type, size, weight, speed, and operating capabilities to those in this petition.

Additionally, the FAA has finalized the first operational rules for routine commercial use of small unmanned aircraft systems (sUAS) (part 107, Operation and Certification of Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems). The new rule, which went into effect August 29, 2016, offers safety regulations for sUAS weighing less than 55 pounds that are conducting non-hobbyist operations. The vast majority of operations authorized under previously-issued exemptions under Section 333 have been addressed by part 107; now that part 107 is in effect, these operations do not necessitate an exemption. However, your Section 333 exemption remains valid until it expires. You may continue to fly following the Conditions and Limitations in your exemption and under the terms of a Certificate of Waiver or Authorization (COA). If your operation can be conducted under the requirements in part 107, you may elect to operate under part 107; however, if you wish to operate under part 107, you must obtain a remote pilot certificate and follow the operating rules of part 107. For more information, please visit: http://www.faa.gov/uas/.

The Basis for Our Decision

The FAA has previously issued a grant of exemption for relief from §§ 61.23(a) and (c), 61.101(e)(4) and (5), 61.113(a), 61.315(a), 91.7(a), 91.119(c), 91.121, 91.151(a)(1), 91.405(a), 91.407(a)(1), 91.409(a)(1) and (2), and 91.417(a) and (b) of Title 14, Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR). That exemption allows the operators to operate UAS to perform aerial data collection or aerial data collection and closed-set filming and television production.

The FAA has revised the Conditions and Limitations issued in exemptions authorizing unmanned aircraft operations under Section 333 since the petitioner’s previous grant of exemption to those found in Exemption No. 15005 to Thomas R. Guilmette (see Docket No. FAA-2015-5829). Also in Exemption Nos. 13465A to Kansas State University (see Docket No. FAA-2014-1088), 11433A to Cape Productions (see Docket No. FAA-2015-0223), 11213 to Aeryon Labs, Inc. (see Docket No. FAA-2014-0642), 11062 to Astraeus Aerial (see Docket No. FAA−2014−0352), 11109 to Clayco, Inc. (see Docket No. FAA−2014−0507), 11112 to VDOS Global, LLC (see Docket No. FAA−2014−0382), the FAA found that the enhanced safety achieved using a sUAS with the specifications described by the petitioner and carrying no passengers or crew, rather than a manned aircraft of significantly greater proportions, carrying crew and flammable fuel, gives the FAA good cause to find that the UAS operation enabled by this exemption is in the public interest.

Our Decision

The FAA has modified the Conditions and Limitations to address aircraft, training, tethered operations, aircraft registration, and flight operations near persons, vessels, vehicles, and structures. Additionally, in previous exemptions, the FAA limited UAS operations to outside 5 nautical miles of an airport reference point (ARP) as denoted in the current FAA Airport/Facility Directory (AFD) or for airports not denoted with an ARP, the center of the airport symbol as denoted on the current FAA-published aeronautical chart unless a letter of agreement (LOA) with that airport’s management is obtained or otherwise permitted by a COA issued to the exemption holder. The FAA has removed that condition. In order to maintain safety in the vicinity of airports in Class B, C, or D airspace, the petitioner must apply to the Air Traffic Organization (ATO) for a new or amended COA. The FAA has determined that the justification for the issuance of Section 333 exemptions remains valid and is in the public interest. Therefore, under the authority contained in 49 U.S.C. 106(f), 40113, and 44701, delegated to me by the Administrator, the operator is granted an amendment to its exemption from 14 CFR §§ 61.23(a) and (c), 61.101(e)(4) and (5), 61.113(a), 61.315(a), 91.7(a), 91.119(c), 91.121, 91.151(a)(1), 91.405(a), 91.407(a)(1), 91.409(a)(1) and (2), and 91.417(a) and (b), to the extent necessary to allow the petitioner to conduct UAS operations. This exemption is subject to the Conditions and Limitations listed below.The list of affected docket numbers is included in Appendix A. The operator shall add this amendment to all previously-issued exemption(s). Without the original exemption and all subsequent amendments, this amendment is not valid.

Conditions and Limitations

The Conditions and Limitations within the previously-issued grant of exemptions have been superseded, and are amended as follows. Failure to comply with any of the Conditions and Limitations of this grant of exemption will be grounds for the immediate suspension or rescission of this exemption.

- The operator is authorized by this grant of exemption to use any aircraft identified on the List of Approved Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) under Section 333 at regulatory docket FAA–2007–3330 at www.regulations.gov, when weighing less than 55 pounds including payload. Proposed operations of any aircraft not on the list currently posted to the above docket will require a new petition or a petition to amend this exemption.

- If operations under this exemption involve the use of foreign civil aircraft the operator would need to obtain a Foreign Aircraft Permit pursuant to 14 CFR § 375.41 before conducting any commercial air operations under this authority. Application instructions are specified in 14 CFR §375.43. Applications should be submitted by electronic mail to the DOT Office of International Aviation, Foreign Air Carrier Licensing Division. Additional information can be obtained via https://cms.dot.gov/policy/aviation-policy/licensing/foreign-carriers.

- The UA may not be operated at a speed exceeding 87 knots (100 miles per hour). The operator may use either groundspeed or calibrated airspeed to determine compliance with the 87 knot speed restriction. In no case will the UA be operated at airspeeds greater than the maximum UA operating airspeed recommended by the aircraft manufacturer.

- The UA must be operated at an altitude of no more than 400 feet above ground level (AGL). Altitude must be reported in feet AGL. This limitation is in addition to any altitude restrictions that may be included in the applicable COA.

- Air Traffic Organization (ATO) Certificate of Waiver or Authorization (COA). All operations must be conducted in accordance with an ATO-issued COA. The exemption holder must apply for a new or amended COA if it intends to conduct operations that cannot be conducted under the terms of the enclosed COA.

- The Pilot in Command (PIC) must have the capability to maintain visual line of sight (VLOS) at all times. This requires the PIC to be able to use human vision unaided by any device other than corrective lenses, as specified on that individual’s FAA-issued airman medical certificate or valid U.S. driver’s license issued by a state, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, a territory, a possession, or the Federal Government, to see the UA.

- All operations must utilize a visual observer (VO). The UA must be operated within the visual line of sight (VLOS) of the VO at all times. The VO must use human vision unaided by any device other than corrective lenses to see the UA. The VO, the person manipulating the flight controls of the small UAS, and the PIC must be able to communicate verbally at all times. Electronic messaging or texting is not permitted during flight operations. The PIC must be designated before the flight and cannot transfer his or her designation for the duration of the flight. The PIC must ensure that the VO can perform the duties required of the VO. Students receiving instruction or observing an operation as part of their instruction may not serve as visual observers.

- This exemption, the List of Approved Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) under Section 333 at regulatory docket FAA-2007-3330 at www.regulations.gov, all previous grant(s) of exemption, and all documents needed to operate the UAS and conduct its operations in accordance with the Conditions and Limitations stated in this exemption, are hereinafter referred to as the operating documents. The operating documents must be accessible during UAS operations and made available to the Administrator upon request. If a discrepancy exists between the Conditions and Limitations in this exemption, the applicable ATO-issued COA, and the procedures outlined in the operating documents, the most restrictive conditions, limitations, or procedures apply and must be followed. The operator may update or revise its operating documents as necessary. The operator is responsible for tracking revisions and presenting updated and revised documents to the Administrator or any law enforcement official upon request. The operator must also present updated and revised documents if it petitions for extension or amendment to this exemption. If the operator determines that any update or revision would affect the basis upon which the FAA granted this exemption, then the operator must petition for an amendment to its exemption. The FAA’s UAS Integration Office may be contacted if questions arise regarding updates or revisions to the operating documents.

- Any UAS that has undergone maintenance or alterations that affect the UAS operation or flight characteristics, e.g. replacement of a flight critical component, must undergo a functional test flight prior to conducting further operations under this exemption. Functional test flights may only be conducted by a PIC with a VO and essential flight personnel only and must remain at least 500 feet from all other people. The functional test flight must be conducted in such a manner so as to not pose an undue hazard to persons and property.

- The operator is responsible for maintaining and inspecting the UAS to ensure that it is in a condition for safe operation.

- Prior to each flight, the PIC must conduct a pre-flight inspection and determine the UAS is in a condition for safe flight. The pre-flight inspection must account for all potential discrepancies, e.g. inoperable components, items, or equipment. If the inspection reveals a condition that affects the safe operation of the UAS, the aircraft is prohibited from operating until the necessary maintenance has been performed and the UAS is found to be in a condition for safe flight.

- The operator must follow the UAS manufacturer’s maintenance, overhaul, replacement, inspection, and life limit requirements for the aircraft and aircraft components. Each UAS operated under this exemption must comply with all manufacturer safety bulletins.

- PIC certification: Under this grant of exemption, a PIC must hold either an airline transport, commercial, private, recreational, or sport pilot certificate. The PIC must also hold a current FAA airman medical certificate or a valid U.S. driver’s license issued by a state, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, a territory, a possession, or the Federal government. The PIC must also meet the flight review requirements specified in 14 CFR § 61.56 in an aircraft in which the PIC is rated on his or her pilot certificate.

- PIC qualifications: The PIC must demonstrate the ability to safely operate the UAS in a manner consistent with how it will be operated under this exemption, including evasive and emergency maneuvers and maintaining appropriate distances from persons, vessels, vehicles, and structures before conducting student training operations. Flights for the pilot’s own training, proficiency, or experience-building under this exemption may be conducted under this exemption. PIC qualification flight hours and currency may be logged in a manner consistent with 14 CFR § 61.51(b), however, UAS pilots must not log this time in the same columns or categories as time accrued during manned flight. UAS flight time must not be recorded as part of total time.

- Training: The operator may conduct training operations when the trainer/instructor is qualified as a PIC under this exemption and designated as PIC for the entire duration of the flight operation. Students/trainees are considered direct participants in the flight operation when manipulating the flight controls of a small UAS and are not required to hold any airman certificate. The student/trainees may be the manipulators of the controls; however, the PIC must directly supervise their conduct and the PIC must also have sufficient override capability to immediately take direct control of the small UAS and safely abort the operation if necessary, including taking any action necessary to ensure safety of other aircraft as well as persons and property on the ground in the event of unsafe maneuvers and/or emergencies for example landing in an empty area away from people and property.

- Under all situations, the PIC is responsible for the safety of the operation. The PIC is also responsible for meeting all applicable Conditions and Limitations as prescribed in this exemption and ATO-issued COA, and operating in accordance with the operating documents. All training operations must be conducted during dedicated training sessions and may or may not be for compensation or hire. The operation must be conducted with a dedicated VO who has no collateral duties and is not the PIC during the flight. The VO must maintain visual sight of the aircraft at all times during flight operations without distraction in accordance with the Conditions and Limitations below. Furthermore, the PIC must operate the UA not closer than 500 feet to any nonparticipating person without exception.

- UAS operations may not be conducted during night, as defined in 14 CFR § 1.1. All operations must be conducted under visual meteorological conditions (VMC). Flights under special visual flight rules (SVFR) are not authorized.

- The UA may not be operated less than 500 feet below or less than 2,000 feet horizontally from a cloud or when visibility is less than 3 statute miles from the PIC.

- For tethered UAS operations, the tether line must have colored pennants or streamers attached at not more than 50 foot intervals beginning at 150 feet above the surface of the earth and visible from at least 1 mile. This requirement for pennants or streamers is not applicable when operating exclusively below the top of and within 250 feet of any structure, so long as the UA operation does not obscure the lighting of the structure.

- For UAS operations where GPS signal is necessary to safely operate the UA, the PIC must immediately recover/land the UA upon loss of GPS signal.

- If the PIC loses command or control link with the UA, the UA must follow a predetermined route to either reestablish link or immediately recover or land.

- The PIC must abort the flight operation if unpredicted circumstances or emergencies that could potentially degrade the safety of persons or property arise. The PIC must terminate flight operations without causing undue hazard to persons or property in the air or on the ground.

- The PIC is prohibited from beginning a flight unless (considering wind and forecast weather conditions) there is enough available power for the UA to conduct the intended operation and to operate after that for at least five minutes or with the reserve power recommended by the manufacturer if greater.

- All aircraft operated in accordance with this exemption must be registered in accordance with 14 CFR part 47 or 48, and have identification markings in accordance with 14 CFR part 45, Subpart C or part 48.

- Documents used by the operator to ensure the safe operation and flight of the UAS and any documents required under 14 CFR §§ 91.9 and 91.203 must be available to the PIC at the Ground Control Station of the UAS any time the aircraft is operating. These documents must be made available to the Administrator or any law enforcement official upon request.

- The UA must remain clear of and give way to all manned aircraft at all times.

- The UAS may not be operated by the PIC from any moving device or vehicle.

- All flight operations must be conducted at least 500 feet from all persons, vessels, vehicles, and structures unless when operating:

a. Over or near people directly participating in the operation of the UAS. People directly participating in the operation of the UAS include the student manipulating the controls, PIC, VO, and other consenting personnel that are directly participating in the safe operation of the UA.

b. Near but not over people directly participating in the intended purpose of the UAS operation. People directly participating in the intended purpose of the UAS (including students in a class not manipulating the controls of the UAS), who must be briefed on the potential risks and acknowledge and consent to those risks. Operators must notify the local Flight Standards District Office (FSDO) with a plan of activities at least 72 hours prior to flight operations.

c. Near nonparticipating persons: Except as provided in subsections (a) and (b) of this section, a UA may only be operated closer than 500 feet to a person when barriers or structures are present that sufficiently protect that person from the UA and/or debris or hazardous materials such as fuel or chemicals in the event of an accident. Under these conditions, the operator must ensure that the person remains under such protection for the duration of the operation. If a situation arises where the person leaves such protection and is within 500 feet of the UA, flight operations must cease immediately in a manner that does not cause undue hazard to persons.

d. Near vessels, vehicles, and structures. Prior to conducting operations the operator must obtain permission from a person with the legal authority over any vessels, vehicles or structures that will be within 500 feet of the UA during operations. The PIC must make a safety assessment of the risk of operating closer to those objects and determined that it does not present an undue hazard.

29. All operations shall be conducted over private or controlled-access property with permission from a person with legal authority to grant access. Permission will be obtained for each flight to be conducted.

30. Any incident, accident, or flight operation that transgresses the lateral or vertical boundaries of the operational area as defined by the applicable COA must be reported to the FAA’s UAS Integration Office within 24 hours. Accidents must be reported to the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) in accordance with its UAS accident reporting requirements. For operations conducted closer than 500 feet to people directly participating in the intended purpose of the operation, not protected by barriers, the following additional conditions and limitations apply:

31. The operator must have an operations manual that contains at least the following items, although it is not restricted to these items.

a. Operator name, address, and telephone number

b. Distribution and Revision. Procedures for revising and distributing the operations manual to ensure that it is kept current. Revisions must comply with the applicable Conditions and Limitations in this exemption.

c. Persons Authorized. Specify criteria for designating individuals as directly participating in the safe operation of the UAS. The operations manual must include procedures to ensure that all operations are conducted at distances from persons in accordance with the Conditions and Limitations of the exemption.

d. Plan of Activities. The operations manual must include procedures for the submission of a written plan of activities.

e.Permission to Operate. The operations manual shall specify requirements and procedures that the operator will use to obtain permission to operate over property or near vessels, vehicles, and structures in accordance with this exemption.

f. Security. The manual must specify the method of security that will be used to ensure the safety of nonparticipating persons. This should also include procedures that will be used to stop activities when unauthorized persons, vehicles, or aircraft enter the operations area, or for any other reason, in the interest of safety.

g. Briefing of persons directly participating in the intended operation. Procedures must be included to brief personnel and participating persons on the risks involved, emergency procedures, and safeguards to be followed during the operation.

h.Personnel directly participating in the safe operation of the UAS Minimum Requirements. In accordance with this exemption, the operator must specify the minimum requirements for all flight personnel in the operating manual. The PIC at a minimum will be required to meet the certification standards specified in this exemption.

i. Communications. The operations manual must contain procedures to provide communications capability with participants during the operation. The operator can use oral, visual, or radio communications as along as the participants are apprised of the current status of the operation.

j. Accident Notification. The operations manual must contain procedures for notification and reporting of accidents in accordance with this exemption. In accordance with this exemption, the operating manual and all other operating documents must be accessible to the PIC during UAS operations.

32.At least 72 hours prior to operations, the operator must submit a written Plan of Activities to the local FSDO having jurisdiction over the proposed operating area. The Plan of Activities must include at least the following:

a. Dates and times for all flights. For seasonal or long-term operations, this can include the beginning and end dates of the timeframe, the approximate frequency (e.g. daily, every weekend, etc.), and what times of the day operations will occur. A new plan of activities must be submitted prior to each season or period of operations.

b. Name and phone number of the on-site person responsible for the operation.

c. Make, model, and serial or FAA registration number of each UAS to be used.

d.Name and certificate number of each UAS PIC involved in the operations.

e. A statement that the operator has obtained permission from property owners. Upon request, the operator will make available a list of those who gave permission.

f. Signature of exemption holder or representative stating the plan is accurate.

g. A description of the flight activity, including maps or diagrams of the area over which operations will be conducted and the altitudes essential to accomplish the operation.

Unless otherwise specified in this exemption, the UAS, the UAS PIC, and the UAS operations must comply with all applicable parts of 14 CFR including, but not limited to, parts 45, 47, 48, 61, and 91. This exemption terminates on the date provided in the petitioner’s original exemption or amendment most recently granted prior to the date of this amendment, unless sooner superseded or rescinded.

Example of a Blanket COA

A. General.

1. The approval of this COA is effective only with an approved Section 333 FAA Grant of Exemption.

2. A copy of the COA including the special limitations must be immediately available to all operational personnel at each operating location whenever UAS operations are being conducted.

3. This authorization may be canceled at any time by the Administrator, the person authorized to grant the authorization, or the representative designated to monitor a specific operation. As a general rule, this authorization may be canceled when it is no longer required, there is an abuse of its provisions, or when unforeseen safety factors develop. Failure to comply with the authorization is cause for cancellation. The operator will receive written notice of cancellation.

B. Safety of Flight.

1. The operator or pilot in command (PIC) is responsible for halting or canceling activity in the COA area if, at any time, the safety of persons or property on the ground or in the air is in jeopardy, or if there is a failure to comply with the terms or conditions of this authorization.

See-and-Avoid

Unmanned aircraft have no on-board pilot to perform see-and-avoid responsibilities; therefore, when operating outside of active restricted and warning areas approved for aviation activities, provisions must be made to ensure an equivalent level of safety exists for unmanned operations consistent with 14 CFR Part 91 §91.111, §91.113 and §91.115.

a. The pilot in command (PIC) is responsible:

-To remain clear and give way to all manned aviation operations and activities at all times,

-For the safety of persons or property on the surface with respect to the UAS, and

-For compliance with CFR Parts 91.111, 91.113 and 91.115

b. UAS pilots will ensure there is a safe operating distance between aviation activities and unmanned aircraft (UA) at all times.

c. Visual observers must be used at all times and maintain instantaneous communication with the PIC.

d. The PIC is responsible to ensure visual observer(s) are:

-Able to see the UA and the surrounding airspace throughout the entire flight, and

-Able to provide the PIC with the UA’s flight path, and proximity to all aviation activities and other hazards (e.g., terrain, weather, structures) sufficiently for the PIC to exercise effective control of the UA to prevent the UA from creating a collision hazard.

e. Visual observer(s) must be able to communicate clearly to the pilot any instructions required to remain clear of conflicting traffic.

2. Pilots are reminded to follow all federal regulations e.g. remain clear of all Temporary Flight Restrictions, as well as following the exemption granted for their operation.

3. The operator or delegated representative must not operate in Prohibited Areas, Special Flight Rule Areas or, the Washington National Capital Region Flight Restricted Zone,

except operations in the Washington DC Special Flight Rule Area may be approved only with prior coordination with the Security Operations Support Center (SOSC) at 202-267- 8276. Such areas are depicted on charts available at http://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/flight_info/aeronav/. Additionally, aircraft operators should beware of and avoid other areas identified in Notices to Airmen (NOTAMS) which restricts operations in proximity to Power Plants, Electric Substations, Dams, Wind Farms, Oil Refineries, Industrial Complexes, National Parks, The Disney Resorts, Stadiums, Emergency Services, the Washington DC Metro Flight Restricted Zone, Military or other Federal Facilities.

4. The unmanned aircraft will be registered prior to operations in accordance with Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations.

C. Reporting Requirements

1. Documentation of all operations associated with UAS activities is required regardless of the airspace in which the UAS operates. NOTE: Negative (zero flights) reports are required.

2. The operator must submit the following information through mailto:[email protected] on a monthly basis:

a. Name of Operator, Exemption number and Aircraft registration number

b. UAS type and model

c. All operating locations, to include location city/name and latitude/longitude

d. Number of flights (per location, per aircraft)

e. Total aircraft operational hours

f. Takeoff or Landing damage

g. Equipment malfunctions. Reportable malfunctions include, but are not limited to the following:

(1) On-board flight control system

(2) Navigation system

(3) Power plant failure in flight

(4) Fuel system failure

(5) Electrical system failure

(6) Control station failure

3. The number and duration of lost link events (control, performance and health monitoring, or communications) per UA per flight.

4. Incident/Accident/Mishap Reporting After an incident or accident that meets the criteria below, and within 24 hours of that incident, accident or event described below, the proponent must provide initial notification of the following to the FAA via email at [email protected] and via the UAS COA On-Line forms (Incident/Accident).

1. All accidents/mishaps involving UAS operations where any of the following occurs:

a. Fatal injury, where the operation of a UAS results in a death occurring within 30 days of the accident/mishap

b. Serious injury, where the operation of a UAS results in: (1) hospitalization for more than 48 hours, commencing within 7 days from the date of the injury was received; (2) results in a fracture of any bone (except simple fractures of fingers, toes, or nose); (3) causes severe hemorrhages, nerve, muscle, or tendon damage; (4) involves any internal organ; or (5) involves second- or third-degree burns, orany burns affecting more than 5 percent of the body surface.

c. Total unmanned aircraft loss

d. Substantial damage to the unmanned aircraft system where there is damage to the airframe, power plant, or onboard systems that must be repaired prior to further flight

e. Damage to property, other than the unmanned aircraft.

2. Any incident/mishap that results in an unsafe/abnormal operation including but not limited to

a. A malfunction or failure of the unmanned aircraft’s on-board flight control system (including navigation)

b. A malfunction or failure of ground control station flight control hardware or software (other than loss of control link)

c. A power plant failure or malfunction

d. An in-flight fire

e. An aircraft collision involving another aircraft.

f. Any in-flight failure of the unmanned aircraft’s electrical system requiring use of alternate or emergency power to complete the flight

g. A deviation from any provision contained in the COA

h. A deviation from an ATC clearance and/or Letter(s) of Agreement/Procedures

i. A lost control link event resulting in

(1) Fly-away, or

(2) Execution of a pre-planned/unplanned lost link procedure.

3. Initial reports must contain the information identified in the COA On-Line Accident/Incident Report.

4. Follow-on reports describing the accident/incident/mishap(s) must be submitted by providing copies of proponent aviation accident/incident reports upon completion of safety investigations.

5. Civil operators and Public-use agencies (other than those which are part of the Department of Defense) are advised that the above procedures are not a substitute for separate accident/incident reporting required by the National Transportation Safety Board under 49 CFR Part 830 §830.5.

6. For other than Department of Defense operations, this COA is issued with the provision that the FAA be permitted involvement in the proponent’s incident/accident/mishap investigation as prescribed by FAA Order 8020.11, Aircraft Accident and Incident Notification, Investigation, and Reporting.

D. Notice to Airmen (NOTAM). A distant (D) NOTAM must be issued when unmanned aircraft operations are being conducted. This requirement may be accomplished:

a. Through the operator’s local base operations or NOTAM issuing authority, or

b. By contacting the NOTAM Flight Service Station at 1-877-4-US-NTMS (1-877-487- 6867) not more than 72 hours in advance, but not less than 24 hours prior to the operation, unless otherwise authorized as a special provision. The issuing agency will require the:

(1) Name and address of the pilot filing the NOTAM request

(2) Location, altitude, or operating area

(3) Time and nature of the activity.

(4) Number of UAS flying in the operating area.

AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL SPECIAL PROVISIONS

A. Coordination Requirements.

1. Operators and UAS equipment must meet the requirements (communication, equipment and clearance) of the class of airspace they will operate in.

2. Operator filing and the issuance of required distance (D) NOTAM, will serve as advance ATC facility notification of UAS operations in an area.

3. The area of operation defined in the NOTAM must only be for the actual area to be flown for each day defined by a point and the minimum radius required to conduct the operation.

4. Operator must cancel NOTAMs when UAS operations are completed or will not be conducted.

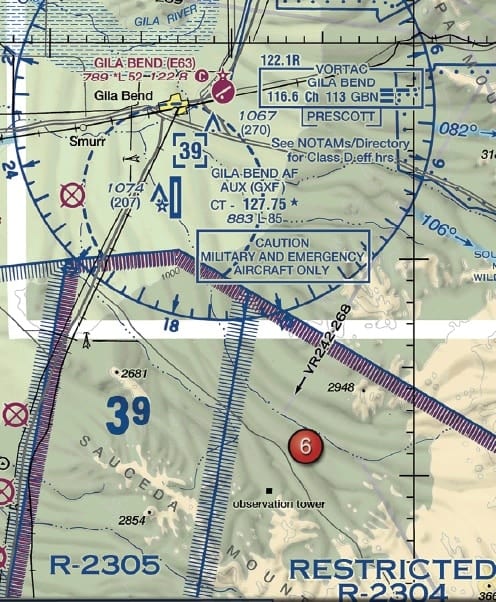

5. Coordination and de-confliction between Military Training Routes (MTRs) is the operator’s responsibility. When identifying an operational area the operator must evaluate whether an MTR will be affected. In the event the UAS operational area overlaps an MTR, the operator will contact the scheduling agency 24 hours in advance to coordinate and de-conflict. Approval from the scheduling agency is not required. Scheduling agencies are listed in the Area Planning AP/1B Military Planning Routes North and South America, if unable to gain access to AP/1B contact the FAA at email address [email protected] with the IR/VR routes affected and the FAA will provide the scheduling agency information. If prior coordination and de-confliction does not take place 24 hours in advance, the operator must remain clear of all MTRs.

B. Communication Requirements. When operating in the vicinity of an airport without an operating control tower, announce your operations in accordance with the FAA Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM) 4-1- 9 Traffic Advisory Practices at Airports without Operating Control Towers.

C. Flight Planning Requirements.

Note: For all UAS requests not covered by the conditions listed below, the exemption holder may apply for a new Air Traffic Organization (ATO) Certificate of Waiver or

Authorization (COA) at https://oeaaa.faa.gov/oeaaa/external/uas/portal.jsp This COA will allow small UAS (55 pounds or less) operations during daytime VFR conditions under the following conditions and limitations:

(1) At or below 400 feet AGL; and

(2) Beyond the following distances from the airport reference point (ARP) of a public use airport, heliport, gliderport, or seaport listed in the Airport/Facility Directory, Alaska Supplement, or Pacific Chart Supplement of the U.S. Government Flight Information Publications.

a) 5 nautical miles (NM) from an airport having an operational control tower; or

b) 3 NM from an airport having a published instrument flight procedure, but not

having an operational control tower; or

c) 2 NM from an airport not having a published instrument flight procedure or an

operational control tower; or

d) 2 NM from a heliport

D. Emergency/Contingency Procedures.

1. Lost Link/Lost Communications Procedures:

a. If the UAS loses communications or loses its GPS signal, the UA must return to a pre-determined location within the private or controlled-access property and land.

b. The PIC must abort the flight in the event of unpredicted obstacles or emergencies.

2. Any incident, accident, or flight operation that transgresses the lateral or vertical boundaries defined in this COA must be reported to the FAA via email at [email protected] within 24 hours. Accidents must be

reported to the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) per instructions contained on the NTSB Web site: www.ntsb.gov

AUTHORIZATION

This Certificate of Waiver or Authorization does not, in itself, waive any Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations, nor any state law or local ordinance. Should the proposed operation conflict with any state law or local ordinance, or require permission of local authorities or property owners, it is the responsibility of the operator to resolve the matter. This COA does not authorize flight within Special Use airspace without approval from the scheduling agency. The operator is hereby authorized to operate the small Unmanned Aircraft System in the National Airspace System.

Example of a Public “Blanket” COA (Version 1.0 ~ Mid-Late 2016)

I. STANDARD PROVISIONS

A. General.

The review of this activity is based upon current understanding of Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) operations and their impact on the National Airspace System (NAS).This Certificate of Waiver or Authorization (COA) will not be considered a precedent for future operations. As changes in, or understanding of, UAS operations occur, the associated limitations and conditions may be adjusted.

All personnel engaged in the operation of the UAS in accordance with this authorization must read and comply with the conditions, limitations, and provisions of this COA.

A copy of the COA including the special limitations must be immediately available to all operational personnel at each operating location whenever UAS operations are being conducted.

This COA may be canceled at any time by the Administrator, a person authorized to grant the authorization, or a representative designated to monitor a specific operation. As a general rule, this authorization may be canceled when it is no longer required, when there is an abuse of its provisions, or when unforeseen safety factors develop. Failure to comply with the authorization is cause for cancellation. All cancellations will be provided in writing to the proponent.

During the time this COA is approved and active, a site safety evaluation/visit may be accomplished to ensure COA compliance, assess any adverse impact on ATC or airspace, and ensure this COA is not burdensome or ineffective. Deviations, accidents/incidents/mishaps, complaints, etc. will prompt a COA review or site visit to address the issue. Refusal to allow a site safety evaluation/visit may result in cancellation of the COA. Note: This section does not pertain to agencies that have other existing agreements in place with the FAA.

Public Aircraft Operations are defined by statutes Title 49 USC §40102(a)(41) and §40125. All public aircraft operations conducted under a COA must comply with the terms of the statutes.

B. Airworthiness Certification.

The unmanned aircraft must be shown to be airworthy to conduct flight operations in the NAS. The proponent has made its own determination that the unmanned aircraft is airworthy. The unmanned aircraft must be operated in strict compliance with all provisions and conditions contained in the Airworthiness Safety Release (AWR), including all documents and provisions referenced in the COA application.

1. A configuration control program must be in place for hardware and/or software changes made to the UAS to ensure continued airworthiness. If a new or revised Airworthiness Release is generated as a result of changes in the hardware or software affecting the operating characteristics of the UAS, notify the UAS Integration Office via email at 9- [email protected] of the changes as soon as practical.

a. Software and hardware changes should be documented as part of the normal maintenance procedures. Software changes to the aircraft and control station as well as hardware system changes are classified as major changes unless the agency has a formal process accepted by the FAA. These changes should be provided to the UAS Integration Office in summary form at the time of incorporation.

b. Major modifications or changes, performed under the COA, or other authorizations that could potentially affect the safe operation of the system, must be documented and provided to the FAA in the form of a new AWR, unless the agency has a formal process, accepted by the FAA.

c. All previously flight proven systems, to include payloads, may be installed or removed as required and that activity must be recorded in the unmanned aircraft and ground control stations logbooks by persons authorized to conduct UAS maintenance. Describe any payload equipment configurations in the UAS logbook that will result in a weight and balance change, electrical loads, and or flight dynamics, unless the agency has a formal process, accepted by the FAA.

d. For unmanned aircraft system discrepancies, a record entry should be made by an appropriately rated person to document the finding in the logbook. No flights may be conducted following major changes, modifications or new installations unless the party responsible for certifying airworthiness has determined the system is safe to operate in the NAS and a new AWR is generated, unless the agency has a formal process, accepted by the FAA. The successful completion of these major changes, modifications or new installations must be recorded in the appropriate logbook, unless the agency has a formal process, accepted by the FAA.

2. The unmanned aircraft must be operated in strict compliance with all provisions and conditions contained within the spectrum analysis assigned and authorized for use within the defined operations area.

3. All items contained in the application for equipment frequency allocation must be adhered to, including the assigned frequencies and antenna equipment characteristics. A ground operational check to verify that the control station can communicate with the aircraft (frequency integration check) must be conducted prior to the launch of the unmanned aircraft to ensure any electromagnetic interference does not adversely affect control of the aircraft.

C. Safety of Flight.

1. The Proponent or delegated representative is responsible for halting or canceling activity conducted under the provisions of this COA if, at any time, the safety of persons or property on the ground or in the air is in jeopardy, or if there is a failure to comply with the terms or conditions of this authorization.

2. Sterile Cockpit Procedures.

a. No crewmember may perform any duties during a critical phase of flight not required for the safe operation of the aircraft.

b. Critical phases of flight include all ground operations involving:

1) Taxi (movement of an aircraft under its own power on the surface of an airport),

2) Take-off and landing (launch or recovery), and

3) All other flight operations in which safety or mission accomplishment might be compromised by distractions.

c. No crewmember may engage in, nor may any pilot in command (PIC) permit, any activity during a critical phase of flight which could:

1) Distract any crewmember from the performance of his/her duties, or

2) Interfere in any way with the proper conduct of those duties.

d. The pilot and/or the PIC must not engage in any activity not directly related to the operation of the aircraft. Activities include, but are not limited to: operating UAS sensors or other payload systems.

e. The use of cell phones or other electronic devices is restricted to communications pertinent to the operational control of the unmanned aircraft and any required communications with Air Traffic Control.

3. See-and-Avoid.

a. Unmanned aircraft have no on-board pilot to perform see-and-avoid responsibilities; therefore, when operating outside of active restricted and warning areas approved for aviation activities, provisions must be made to ensure that an equivalent level of safety exists for unmanned operations. Adherence to 14 CFR Part 91 §91.111, §91.113 and §91.115, is required.

1) The PIC is responsible: To remain clear and give way to all manned aviation operations and activities at all times, For the safety of persons or property on the surface with respect to the UAS operation, For ensuring that there is a safe operating distance between aviation activities and unmanned aircraft (UA) at all times, and For operating in compliance with CFR Parts 91.111, 91.113 and 91.115

b. The PIC is responsible to ensure that any visual observer (VO):

1) Can perform their required duties,

2) Are able to see the UA and the surrounding airspace throughout the entire flight, and 3) Are able to provide the PIC with the UA’s flight path and proximity to all aviation activities and other hazards (e.g., terrain, weather, structures) sufficiently for the PIC to exercise effective control of the UA to prevent the UA from creating a collision hazard.

c. VO(s) must be used at all times and must maintain instantaneous communication with the PIC. Electronic messaging or texting is not permitted during flight operations. d. The use of multiple successive VO(s) (daisy chaining) is prohibited.

e. VO(s) must be able to communicate clearly to the PIC any instructions required to remain clear of conflicting traffic.

f. All VO(s) must complete sufficient training to communicate to the PIC any information required to remain clear of conflicting traffic, terrain, and obstructions, maintain proper cloud clearances, and provide navigational awareness. This training, at a minimum, must include knowledge of:

1) Their responsibility to assist PICs in complying with the requirements of: Section 91.111, Operating Near Other Aircraft, Section 91.113, Right-of-Way Rules: Except Water Operations, Section 91.115, Right-of-Way Rules: Water Operations, Section 91.119, Minimum Safe Altitudes: General, and Section 91.155, Basic VFR Weather Minimums

2) Air traffic and radio communications, including the use of approved air traffic control/pilot phraseology

3) Appropriate sections of the Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM)

g. The Proponent must not operate in Restricted Areas, Prohibited Areas, Special Flight Rule Areas or the Washington DC Flight Restricted Zone. Such areas are depicted on charts available at http://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/flight_info/aeronav/. Additionally, aircraft operators should beware of and avoid other areas identified in Notices to Airmen (NOTAMS) that restrict operations in proximity to Power Plants, Electric Substations, Dams, Wind Farms, Oil Refineries, Industrial Complexes, National Parks, The Disney Resorts, Stadiums, Emergency Services, Military or other Federal Facilities unless approval is received from the appropriate authority prior to the UAS Mission. h. The unmanned aircraft will be registered prior to operations in accordance with Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations.

D. Reporting Requirements

1. Documentation of all operations associated with UAS activities is required regardless of the airspace in which the UAS operates. NOTE: Negative (zero flights) reports are required.

2. The Proponent must submit the following information on a monthly basis to [email protected] :

a. Name of Proponent, and aircraft registration number,

b. UAS type and model,

c. All operating locations, to include city name and latitude/longitude,

d. Number of flights (per location, per aircraft),

e. Total aircraft operation hours,

f. Takeoff or landing damage, and

g. Equipment malfunction. Required reports include, but are not limited to, failures or malfunctions to the:

(1) Control station (2) Electrical system (3) Fuel system (4) Navigation system (5) On-board flight control system (6) Powerplant

3. The number and duration of lost link events (control, performance and health monitoring, or communications) per UAS, per flight.

4. Incident/Accident/Mishap Reporting After an incident or accident that meets the criteria below, and within 24 hours of that incident, accident or event described below, the proponent must provide initial notification of the following to the FAA via email at mailto: 9-AJV-115- [email protected] and via the UAS COA On-Line forms (Incident/Accident).

a. All accidents/mishaps involving UAS operations where any of the following occurs:

1) Fatal injury, where the operation of a UAS results in a death occurring within 30 days of the accident/mishap

2) Serious injury, where the operation of a UAS results in: Hospitalization for more than 48 hours, commencing within 7 days from the date of the injury was received; A fracture of any bone (except simple fractures of fingers, toes, or nose); Severe hemorrhages, nerve, muscle, or tendon damage; Involving any internal organ; or Involves second- or third-degree burns, or any burns affecting more than 5 percent of the body surface.

3) Total unmanned aircraft loss

4) Substantial damage to the unmanned aircraft system where there is damage to the airframe, power plant, or onboard systems that must be repaired prior to further flight

5) Damage to property, other than the unmanned aircraft.

b. Any incident/mishap that results in an unsafe/abnormal operation including but not limited to

1) A malfunction or failure of the unmanned aircraft’s on-board flight control system (including navigation)

2) A malfunction or failure of ground control station flight control hardware or software (other than loss of control link)

3) A power plant failure or malfunction

4) An in-flight fire

5) An aircraft collision involving another aircraft.

6) Any in-flight failure of the unmanned aircraft’s electrical system requiring use of alternate or emergency power to complete the flight

7) A deviation from any provision contained in the COA

8) A deviation from an ATC clearance and/or Letter(s) of Agreement/Procedures

9) A lost control link event resulting in Fly-away, or Execution of a pre-planned/unplanned lost link procedure. c. Initial reports must contain the information identified in the COA On-Line Accident/Incident Report.

d. Follow-on reports describing the accident/incident/mishap(s) must be submitted by providing copies of proponent aviation accident/incident reports upon completion of safety investigations.

e. Civil operators and Public-use agencies (other than those which are part of the Department of Defense) are advised that the above procedures are not a substitute for separate accident/incident reporting required by the National Transportation Safety Board under 49 CFR Part 830 §830.5.

f. For other than Department of Defense operations, this COA is issued with the provision that the FAA be permitted involvement in the proponent’s incident/accident/mishap investigation as prescribed by FAA Order 8020.11, Aircraft Accident and Incident Notification, Investigation, and Reporting.

E. Notice to Airmen (NOTAM).

1. A distant (D) NOTAM must be issued prior to conducting UAS operations. This requirement may be accomplished:

a. Through the proponent’s local base operations or NOTAM issuing authority, or

b. By contacting the NOTAM Flight Service Station at 1-877-4-US-NTMS (1- 877-487- 6867) not more than 72 hours in advance, but not less than 24 hours for UAS operations prior to the operation. The issuing agency will require the:

1) Name and address of the pilot filing the NOTAM request

2) Location, altitude and operating area

3) Time and nature of the activity. Note: The NOTAM must identify actual coordinates and a Radial/DME fix of a prominent navigational aid, with a radius no larger than that where visual line of sight with the UA can be maintained. The NOTAM must be filed to indicate the defined operations area and periods of UA activity. NOTAMs for generalized, wide-area, or continuous periods are not acceptable.

II. FLIGHT STANDARDS SPECIAL PROVISIONS Failure to comply with any of the conditions and limitations of this COA will be grounds for the immediate suspension or cancellation of this COA.

1. Operations authorized by this COA are limited to UAS weighing less than 55 pounds, including payload. Proposed operations of any UAS weighing more than 55 pounds will require the Proponent to provide the FAA with a new airworthiness Certificate (if necessary), Registration N-Number, Aircraft Description, Control Station, Communication System Description, Picture of UAS and any Certified TSO components. Approval to operate the new UAS is contingent on acknowledgement from FAA of receipt of acceptable documentation.

2. External Load Operations, dropping or spraying aircraft stores, or carrying hazardous materials (including munitions) is prohibited.

3. The UA may not be operated at a speed exceeding 87 knots (100 miles per hour). The COA holder may use either groundspeed or calibrated airspeed to determine compliance with the 87 knot speed restriction. In no case will the UA be operated at airspeeds greater than the maximum operating airspeed recommended by the aircraft manufacturer.